It is the middle of one heavy-duty reading for the theoretical background for my first classroom research. I am already a bit tired because it takes time for a rookie scholar (if we want to use big words, if not – just a humble MA student). The eyes are struggling, the brain is struggling, even the spine is struggling because it’s been quite a few articles on the Zone of Proximal Development since the day broke. And, sadly, not all of them exciting. Alas.

But then, somehow, I opened a piece by H. Nassaji and A.Cummings from a few years back *) and, all of a sudden, I was wide awake and excited!

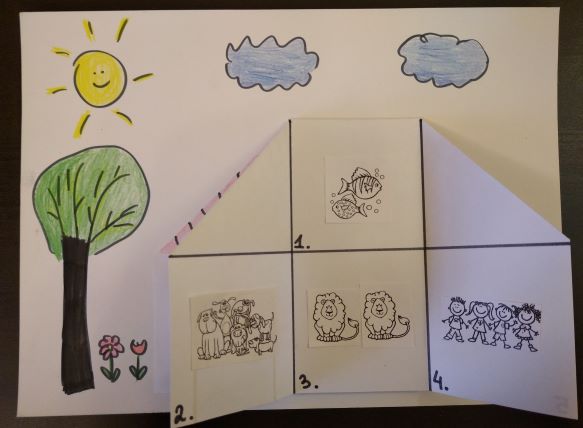

Why? The article is an account of a small-scale but very interesting research based on the dialogue journals that a primary school teacher set up for one of her young students – a 6-year-old boy from an immigrant family who already spoke English at the point of their arrival in Canada but he still struggled in comparison with his peers at school. The journals were a supplementary homework task and their main aim was an opportunity to develop the child’s literacy skills, catered to his immediate needs. The article is fascinating account of the nature of the Zone of Proximal Development and how it was changing in relation to the child developing langauge skills. Highly recommened!

This is how my researcher’s brain reacted. My teacher’s brain only sighed ‘I WANT ONE OF THOSE!’

And I got one. It’s been three years now and this is one of my favourite teaching projects. This is how we do it.

Ingredients

The main aim of this project is the development of young learners’ literacy skills, reading and writing. I normally start this project with my Starters students (that is the children who have finished the YLE Starters level and are about to start preparing for Movers, or, in other words, are at the start of the A1 level). The reasoning behind that timing is the fact that, most of the time, children can deal with simple tests, write single words or simple sentences within a specific structure (from among those that they are familiar with such as I like, I’ve got, I can) but cannot be considered to be fluent readers or independent writers. Not yet, anyway, but keeping the journal is definitely going to help them become these.

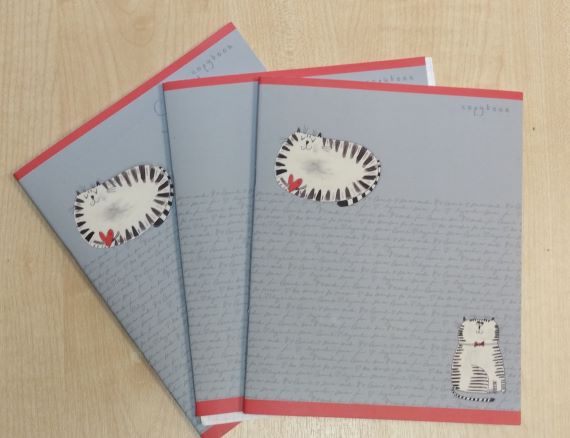

The journals are kept in simple notebooks which I buy for my students. I do not really introduce the idea to the students, apart from a short note, in the kids’ L1, glued into the notebook in which the journal introduces itself. It goes, more or less, like that: Hello! I am your new project – a journal! Please open me, read the notes from Anka and, if you want, write something and bring it back when you are ready! Anka will read it and write something to you!

This time round, since we are all on whatsapp, it was also followed-up by a note to parents which explained in more detail what it is and how I would like to run it.

In each notebook, on the first page, there was the first entry, from me. All of them consisted of only a few lines and said:

Hello student!

How are you? What’s your favourite subject / food / sport / colour / toy?

Write to me!

Anka

Procedures

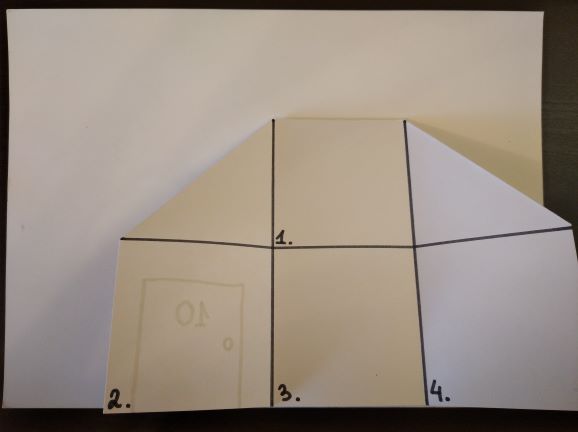

Everything is super simple and straightforward: I give out notebooks, kids take them home, read, reply and bring them back. Then I take them home, read their notes and reply. Afterwards, I take photos of all the entries to keep the record, to be able to reflect on their progress and to save all the data. After all, travelling notebooks are in a grave danger of getting lost in-between the school and the house.

I do not correct any mistakes in the notebooks themselves, not to discourage the kids and not to destroy their entries with my scribbles. Instead, I focus on the delayed error correction and on the extensive input and additional practice based on the mistakes I spot.

It is very important to highlight that I really do not want the journals to become an additonal homework task. The kids are supposed to take part voluntarily and as frequently as they are ready to. In our everyday lesson procedures, whenever we check our regular homework, I also ask ‘Have you got the addional homework?’. I do not keep track of who brought what and when. There are no marks or points involved.

That means that each child is in charge of the journal and of how involved they want to be, they can write a little or a lot, they can write every week or every two weeks, they can draw or not. And, last but not least, they can opt out of being involved altogether.

Reflection

The journals are an amazing opportunity for the kids to develop literacy skills outside of the classroom. Each entry means additional opportunity to read a bit and to write a bit.

All of the entries are highly personalised and unique. The conversations that started from the same ‘What’s your favourite…?’ have taken different routes and turned into conversations about hobbies, families, books, food, sports and pets. Some of them are accompanied by drawings, some of them turned into scrapbooks that both the teacher and the student contribute to. What is more, although there is some scaffolding (ie the questions asked by the teacher), the students have a lot of freedom as regards the topic, the vocabulary and the structures that they want and will use.

They are perfectly suited to the needs of a mixed ability group. I have students who take time to read and to plan what they want to write and later to produce an entry for two pages. I have students who write only one sentence answer and their own question. I had students in the past from whom, at one point, it was easy to supplement the text with simple drawings in order to limit the number of words that they had to write but I was and I am extremely grateful and excited about any, even the smallest contribution.

Regardless of the volume of the text, it is obvious that the kids also learn from the experience as sometimes they write about the topics that are not included in our course curriculum, such as some unusual hobbies, less common although useful verbs etc, and this makes them look up the words in dictionaries which proves that the project also works towards expanding their vocabulary.

What is more, it has been obvious from the very beginning (with different groups) that the students really do enjoy taking part in this project to the point that at one point it even interrupted our classroom routine. As soon as I would give out the journals back to their owners, the kids would grab them, open them and start reading, completely engrossed in it and not paying attention to what was happening in the classroom. Did it upset me? Of course not! I know the feeling – when the book that you are reading is so interesting and so good that you don’t want to put it away. Only this time, it was not a book but our journal and our conversations. I was happy. But I had play with the routine a little bit – on some days I check the homework at the end of the lesson and on some days, we check the homework in two stages, first the homework for all and the journals at the end of the lesson only, depending on the day.

One more lesson learnt is that Kids Can! I am all for challenging the students and hoovering on the outskirts of the ZPD, stretching it gently and carefully but stretching it nonetheless, but since I started this project I have been surprised, time after time. For me, for a long time the main indicator of the students’ writing skills has been the YLE Cambridge tasks and writing assessment scales. While I still consider these to be relevant and useful, thanks to this experience, I was able to see that children, even at the age of 7 and on the level of A1 are capable of a lot more. If given a chance to produce and if the conditions are perfect.

Sample aka a few quotes

‘I’m happy because big holidays.’

‘My favourite food is pasta. I don’t like pasta’

‘My favourite toy is Lego. I like making cars, houses from Lego. I like teddy bears, too. What’s your hobby?’

‘I like to draw magic animals.’

‘I can cook, a little.’

‘I have got many, many, many toys.’

‘I love sharks because they are big and interesting’.

‘My favourite city is Moscow because Moscow is very good and has a lot of big houses.’

The beginning of a beautiful adventure

As I have mentioned above, I have been journaling for three years now, with groups and with individual students, primary and a bit older, too. It has been so successful that I started to use journals in the other areas of teaching and teacher training. More on that soon!

What about the students who don’t want to take part? Nothing. It is their choice and I have respect it. After all, I am this girl who has kept journals since since she was 13 (yes, there are still a few notebooks in my parents’ house, filled up with words, sketches and memories) but not everyone might like writing. Instead, I will encourage, I will praise and I will be completely over the moon when a journal comes back but that’s it. And I will be happy when they do their regular homework and I will absolutely melt when a five-year-old sister of my student also attempts a letter, inspired by our exchanges.

So, how about a journal for your students?

Happy teaching!

*) H. Nassaji and A. Cummings (2000), What’s in a ZPD? A case of a young ESL student and teacher interacting through dialogue journals, Language Teaching Research, 4 (2), p. 95 – 121.