This is the second episode in my Made-up Phrasal Verb series which deals with the different aspects of being a teacher who works with kids. The first one is devoted to stepping out of the shoe of a Miss/Mr Serious Teacher in order to become a human in the classroom, who, first and foremost, cares for the child’s well-being and who takes care of the whole child, which sometimes means putting some (or all?) of the methodology principles on the back burner. You can find the post here.

As it often happens, right after I wrote the post I had an opportunity to ‘practise what you preach’. One of my little students got terribly upset about something she didn’t manage to and right after the class ended, she crawled under her desk and, as a result, I spent some quality time on the floor, in my freshly-washed jeans, under the desk, just hanging out and keeping her company in that difficult moment, until she calmed down. All things considered, it was the most useful thing that I did as a teacher last week…Teachering down full time!

But teachering down is the solution for some of the days and for some of the situations. Sometimes, the teacher needs to do the contrary, to be the real teacher and even more than that. Hence this post.

Teacher up!

Like many of teachers, I follow the social media in order to keep my ears to the ground and to find inspiration for teaching. Then, there are activities that my colleagues and teacher friends share and those that my trainees bring to the course, too. Up until a year ago, there was also the monthly intake of the ‘things I saw in the lessons I observed’ but at the moment, I observe less frequently. Nonetheless, there is a steady inflow of ideas or, in other words, lots of food for thought.

Statistically speaking, a lot of brilliance that can be taken into the classroom directly or after some minor adaptation and it is just great! And if you have any doubts, think about the teacher’s life ten or even twenty years ago when googling ‘ideas for a snowman craft for kindergarten was not an option. Nor was raking through your favourite and trusted bloggers’ accounts for insights. Or sharing a story about a horrible day at school to get a few virtual supportive pats on the shoulder. How did we even live back then?

At the same time, the amount of the seemingly educational material out there is just worrying. There are so many ideas that, at a glance, look like something that would work well, that, on closer inspection turn out to be only ‘the Instagram teaching’, high on the WOW factor, and ‘scraping the bottom of the barrel’ low on methodology and appropriacy as regards the child in the classroom.

Looking at these, the trainer’s eyebrow raises and the teacher’s muscles twitch. And a plethora of questions floods the mind of both. Why did you think it was a good idea for a group of preschoolers? What is the aim for that activity and how is it even connected to everything else in the lesson? Is it in any way appropriate? Generative? Safe? Is it in any way methodologically justifiable? Is there anything to it apart from the WOW materials and WOW photographs that you will be able to post on the social media or send to parents?

Entering the classroom full of pre-school or primary school students, we assume many roles. We become in loco parentis, sometimes a mix of a nanny and a baby-sitter, sometimes more of a governess or a nurse, sometimes a coach, sometimes a witch, sometimes an actor. But, despite all that, first and foremost, we enter the classrooms as teachers.

Teachers who have clear aims for the lesson, linguistic, personal and child development aims, teachers who have thought of the lesson as a whole and all of the puzzles in it, teachers who selected activities and materials with a full awareness of the children’s needs and abilities. There is nothing that ‘just happens to be there’ and even if there is some fluff, it is a well-thought-out and justified fluff that also has a clear aim.

It is a happy coincidence that the first post and these ponderings came at the same time as a series of posts from @abc_academia_ (Katerina Balaganskaya) and @ginger_teacher_efl (Evgeniya Kiseleva) and their project ELT Expert Hub, especially the one about the need for the teachers to focus on good quality continual professional development (see the link in the bibliography). This is all came together. Enthusiasm is great, passion is a must-have, great ideas are precious, optimism and energy in a human make the world go round but, first and foremost, in the classroom, we are teachers. And Michael, a teacher friend, kept sharing the ideas he came across.

Examples? Yes, please. Here are three.

When you are reading them, please remember about my background and context: I am a teacher and a teacher trainer, I work with pre-schoolers and primary school children, who come in groups, possibly fifteen at a time and for most of my students, English is a foreign language whereas for some it is becoming their second language. With some students we have only 2 academic hours of class a week, with some of them we have a lot more but it is in response to a more demanding curriculum. None of my students has a bilingual background or a full-time exposure to English at home. The time in class is precious.

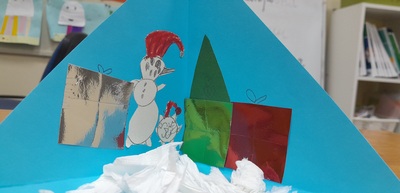

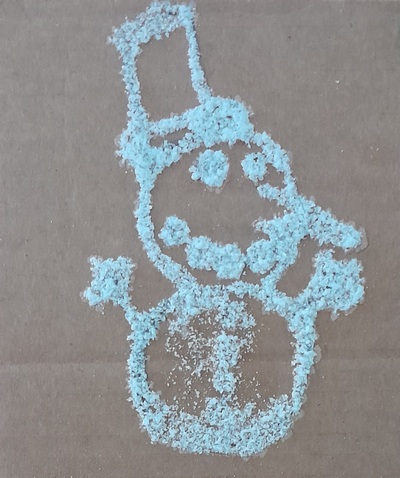

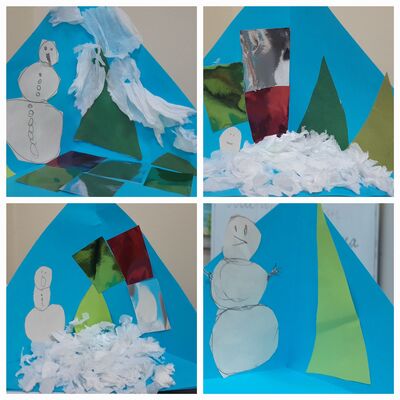

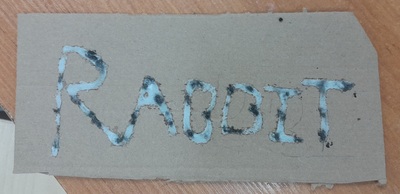

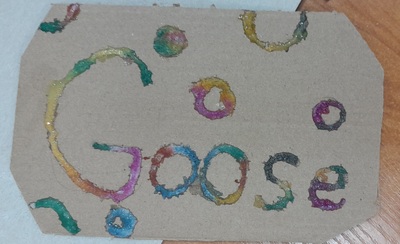

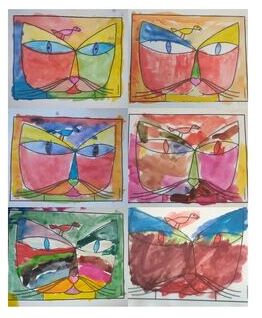

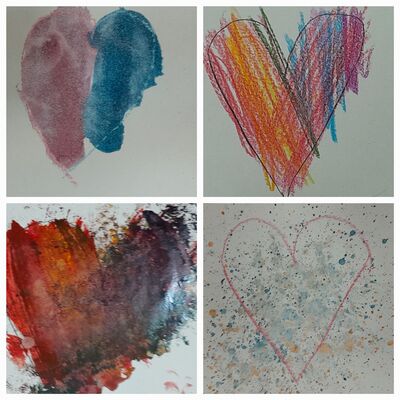

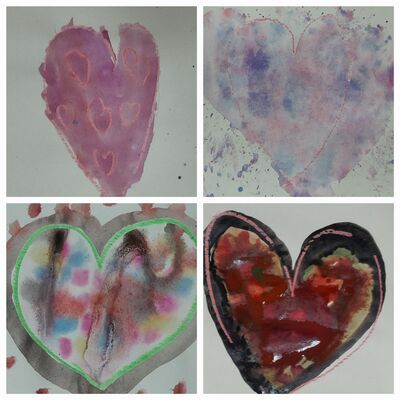

Craft (but NOT for craft’s sake!)

If you are looking for reasons why craft should (and must) be included in the lessons for primary and pre-primary students, you have come to the right place. The best place, I could even risk saying. I love craft at home, I love craft in my classroom and I have already spent a considerable part of my life trying to convince teachers to be a little bit more excited about it. You can read about five reasons of using it in the classroom here and why craft is so important in the VYL world here.

BUT.

Regardless of how much kids love craft activities and of how passionate teachers might be about them, not everything is a lesson-friendly idea and not everything is feasible. Even in a lesson with pre-schoolers, the choice has to be made in connection with and following the methodological principles of teaching English. We are teachers and we walk into classrooms to develop linguistic skills, first and foremost. We need a language aim, we need language production, we need staging and the coherence with the rest of the lesson, the rest of unit and the curriculum. It cannot be ‘just something that we will do’, just something to kill the lesson time, to keep the kids occupied and that will make them go ‘WOW’.

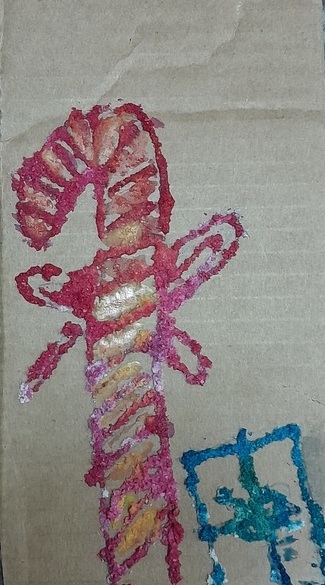

As an example I decided to use the ideas from the video that I found on youtube, on the Gathered Makes channel, here. I actually love all of the ideas presented here but not one of them is a craft that would would work in the language classroom. The tissue paper wreath is pretty and it would really look good on the door or on the window but preparing them would take a painfully large portion of the lesson and it does not offer any opportunities for language production, not even as regards the functional language. A huge part of the task is repetitive and involves sticking on the green tissue and a lot of it so the kids would not be required to ask for different colours or different resources. This would, naturally, lead to a lot L1 in the classroom and, potentially, to some unwanted behaviour. You cannot even ‘talk about’ the different elements of the wreath because it is all just green. The finished product cannot be used in any speaking activity either.

Button candy canes are perfect for the fine motor skills development but I would not want to give out pieces of wire to a group of children, even with a teacher assistant and I would need lots and lots of buttons for the whole group. I am afraid, the little fingers would need help and assistance in the final stage, with tying and fitting in the candy canes and that would simply not work. What’s more, no communicative purpose here and that is one more big disadvantage.

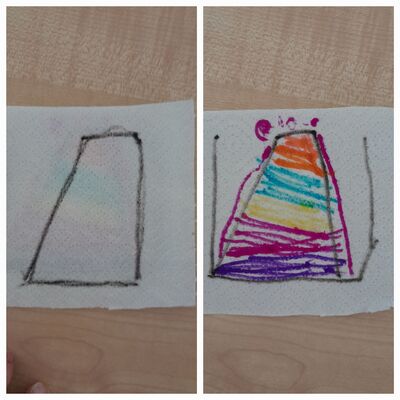

Paper plate Christmas trees look so pretty and they require only the basic resources (the little pompons could be replaced with paint or stickers) but, again, the process is too complicated for a group of primary and pre-primary students. I love the trick with the paper clip here, to keep hold the tree in shape until the glue sets (although I would still use a stapler because I have some serious glue trust issues) but even in the video the child needed the adult’s help with the shaping of the tree. Exactly the same thing would happen in the classroom, and that could mean one pair of two adult and skilled hands AND eight or ten pairs of little hands in need. I have already tried a WOW Christmas tree craft and I simply have to say no here.

Lolly stick snowflakes. No, sorry. Glitter does not enter my classroom. It is probably the single resource that I personally hate. No matter how hard you try and how careful you are, it is tricky to use, it is accidents-prone and it stays with you forever, on the tables, on the body, on the clothes, everywhere. Even if you are using the glitter sticks. And that’s on top of all the other reasons, similar to those mentioned above.

Easy paper decorations are, indeed, easy and fun, as a way of transforming a 2-D shape into a 3-D shape. There is a little bit of cutting (5 circles for a child in the group) and I am not against cutting up things in large quantities to prepare for a lesson but I do when this helps me get lots and lots of language from the children in the proces (for example here). Here, this aim would be difficult to meet. I am not sure about the staging here as painting of the 3-D finished product would be just too messy and, potentially, too frustrating as it would involve holding a half-painted piece and getting fingers dirty and destroying what already has been done.

As mentioned above, I do love all the craft activities but the effort made, the potential complications and the potential for language and the kids’ safety and well-being are absolutely crucial to be taken into consideration. The WOW effect or the pretty photos on the social media cannot be the driving force behind the decision that a teacher makes to include or not to include something in the lesson plan.

If you are looking for any ideas how to plan craft lessons, please have a look at this blog (Chapter: Craft) where I share the ideas from the classroom, tried and tested. I would also like to recommend MadFox which is Carol Read’s creation and six word manual to the principles of craft activities in the classroom. You can read more about it 500 Activities for the Primary Classroom.

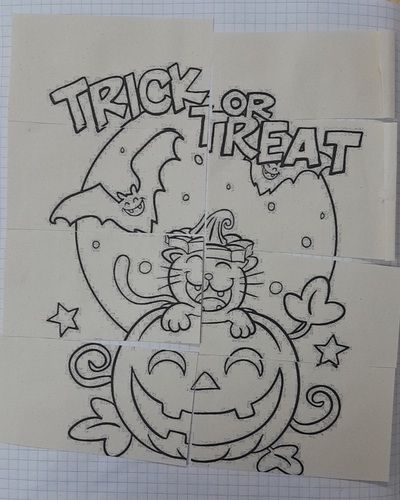

Games. Because educational fun is important

‘Fun’ is one of the most popular words added to titles in education. ‘Young children learn through play’ is probably one of the first things that you will hear in different courses, workshops and trainings devoted to teaching children. It is true, of course, and it applies not only to languages but to all the other skills. This makes our lives much easier and it helps to get the kids interested and keep them involved in the tasks that, at a glace, might be less exciting or those that might involve some hard work. For that reason, only this week, I have decided to teach subtraction to 100 through colouring dictation, through puzzle and through a bunch of reindeer with a serious problem. That is why we have been developing our reading skills through jigsaw puzzles and through Petya, my new invisible student who needed help with his English and that is why I made up a chant about classroom rules. Yes, in a way I was a marketing specialist and an advertising expert, I wanted to sell my product. I did.

In one line: games are good, we need them.

And here is a game that a teacher played with a group of kids in kindergarten. If we had an observation report with the certain standards to observe and to meet, the observer would certainly be able to tick the box: game. Yes, indeed, the teacher prepared a game for the lesson. And that would be all.

Naturally, that is only a small part of the entire lesson and there is no way of knowing what happened before or after and what the aim for the lesson was. However, judging only by this short video, there are quite a few areas for this teacher to work on. It is very difficult why this particular activity was even included in the lesson and what its aims could possibly be. There are no linguistic aims as the kids only do some counting and they use only one colour (orange), only one student is involved at a time while everyone else is watching and it is impossible to figure out whether there were even any child development aims. To be perfectly honest, none of the children taking part seem to be enjoying it and some are even forced to be in, despite their intentions.

If we had to describe the game for someone who did not watch the video, we would have to say that ‘the teacher brings one of the children into the circle, to blow up a balloon and to let the air out right into the children’s ear while the other children are watching and laughing’ and that really turns the category of the activity from a game into ‘a game’. If I had been the observer and the assessor of this lesson, the comments section on the lesson plan or the obervation report would simply say: ‘Please, don’t do this again‘.

A few years ago, there was this tendency at the YL conferences that I happened to attend. Everyone seemed to be criticising the idea of fun in the classroom and replacing it with some other, more serious, methodology-worthy words such as ‘enjoyment’, ‘motivation’ or ‘pleasure’. Maybe it was a trend, maybe just a coincidence but I did not like it. I am up for fun in the classroom, although, for my own personal use and for this blog, I have coined the term: educational fun, to differentiate it from the carefree merry-making.

There is no denying that this carefree merry-making is very necessary in life but since we are teachers, we are obliged (oh-o, the serious words have entered the building) to ensure that we happens in the lesson is deeply rooted in the methodology and child development knowledge that is not only there ‘because because’. Maybe it is true that ‘girls just wanna have fun’ but teachers want to have fun and they also want to smuggle something more while doing it.

To continue with the advertising metaphor from a few paragraphs above, I did have fun but I also had a real product to offer and to promote: a set of classroom rules, a pile of sums and lots and lots of sentences to read and to improve. My students would have done them anyway, we would have to, basically, but it was easier and more pleasant because we did it through and with fun.

Project. What’s love got to do with it?

Here is one more example of the educational path to hell that is paved with very good intentions and the social media teaching that has nothing to do with real classroom methodology but that is extremely photogenic and has ‘WOW’ written all over it. I give you: a CLIL / STEM project devoted to the moon phases.

This is a real example of an activity that one of my teacher friends, Michael, was asked to do with his group and that he happily shared with me, having his own human-adult-fatherly reservations about it. As with the craft activities above, I have nothing against the activity per se but taking it into a classroom full of kids is something that I fail to imagine.

Food allergies aside and the fact that some parents might simply not approve of teachers dishing out sugar portions in class (as, presumably such issues would be dealt with beforehand), there are a few other things that might turn this seemingly amazing and wonderfully appealing project into a complete disaster.

- somebody needs to buy Oreos and in a situation when a school struggles with providing scissors, glue, paper, plasticine and markers, asking for Oreos is just not worth it and might simply not happen. Purchasing them by the teacher is out of the question.

- separating the cookies into two even halves, without breaking them and with the cream staying politely on only one of the sides is…well, I don’t know. It’s been years since I played this way and not with Oreos but with my delicious local equivalent and I just don’t remember. Anyway, we separated them for fun. Our main aim was consumption and we would devour them regardless of how much cream there was on either side. At best, no one can guarantee that all the Oreos for all the kids will comply.

- shaping the cream into the required shape to reflect the phases of the moon is not easy either and it does require something close to surgical precision. And a tool of some sorts (a popsicle stick).

- you are allowed to eat the final product and, hopefully, there is time to talk about the changes and to admire the work done but, ideally, there has to be a lot more Oreos than the number of students x 4 Oreos. Otherwise, we are going to be the cruel people to have the kids work on the cookies, touching them, smelling them but without eating them for a long time and it is a guarantee that not all the kids will be able to stay strong. In the lesson that my friend was asked to teach, the cookies did not last and the model was never made. Either the kids were too hungry or the smell of the cookies too strong, they could not resist. The resources were eaten before the completion of the project. And, to be perfectly honest, I do get it. As an adult, I would struggle myself and I would be tempted to nibble. Or to do a full-on Cookie Monster.

Perhaps it is a fun project to do and a great way of learning about the phases of the moon. For me as a teacher and as a trainer, there are simply too many ‘but’s’ that make it simply not worth the effort. Especially, that there are plenty of other, less high-maintenance and less high-risk and more methodology- and teacher-friendly replacements that can be done with paper, paints, plasticine or ping-pong balls, craft activities and projects that would be more beneficial for the kids.

Coda

We are teachers. We think about the activities that we bring to class.

We are teachers. We respect the parents who trust us with their children and who pay for our teaching skills and the educational process that we provide.

We are teachers. We walk into the classroom with clear lesson aims, linguistic, child development and personal aims, too.

We are teachers. We want to have fun but not for fun’s sake.

We are teachers. First and foremost, we are teachers.

Happy teaching!

Bibliography

Carol Read, 500 Activities for the Primary Classroom, 2007, Macmillan Education

ELT Expert Hub, Evgeniya Kiseleva and Ekaterina Balaganskaya, Teachers’ CPD. https://t.me/eltexperthub