Ingredients

- A3 paper, glue and scissors and a stack of newspapers and journals (gardening, furniture, fashion, kids, music, animals)

- music, for atmoshpere

Procedures

- This lesson in this format was done with my older primary students whose language is on the level of A2 – B1.

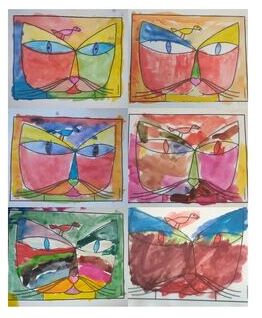

- We started with bringing up Andy Warhol whom we got to know in September (more about this lesson here). As always, it was a pleasure to find out that our Andy Warhol Chebourashka was a very memorable lesson. My students did rememember! We talked about Andy again and especially about his love for Christmas (I do recommend reading about it here).

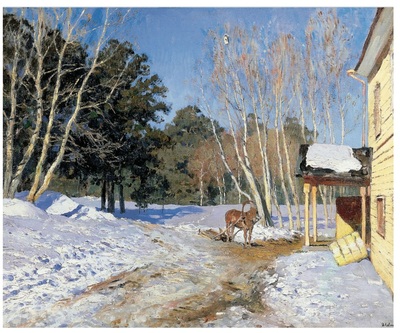

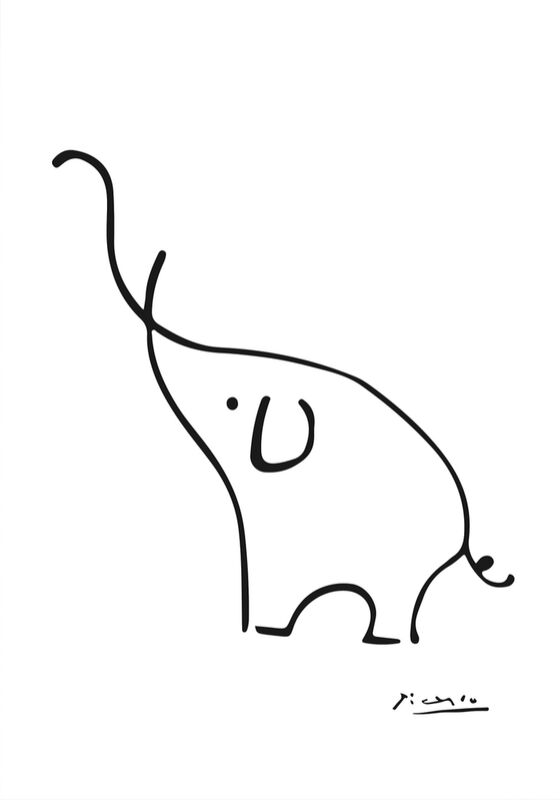

- We looked at the Christmas tree he designed and at the technique (collage).

- Afterwards, I showed all the materials and I started to make my own collage to demonstrate the technique.

- We looked at the journals and newspapers, leafing through to find the theme. I suggested a few (a colour, an object, a topic) and just allowed the kids to think about it.

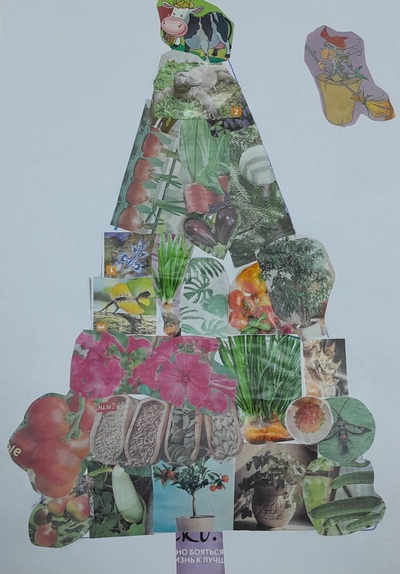

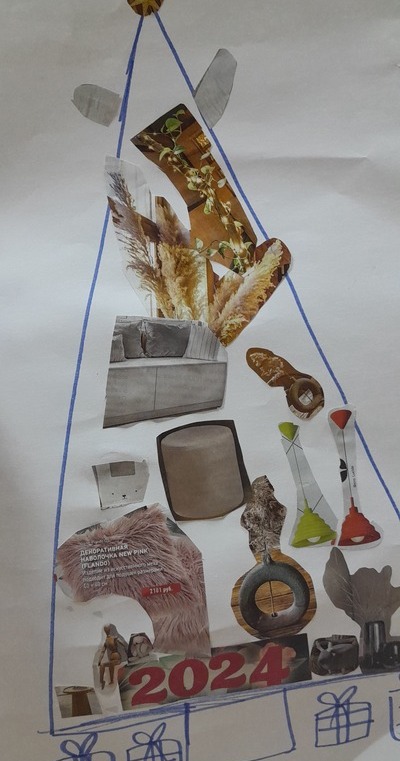

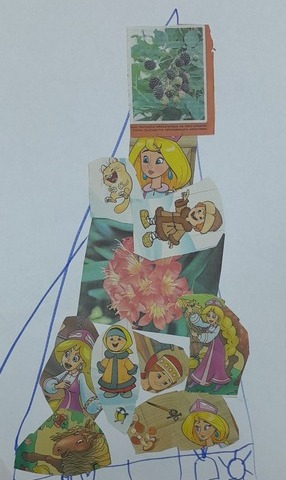

- All this time I was making my own: I drew a big triangle and started glueing the pieces to match my theme (Nature).

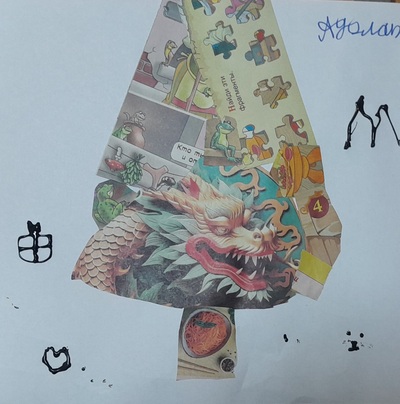

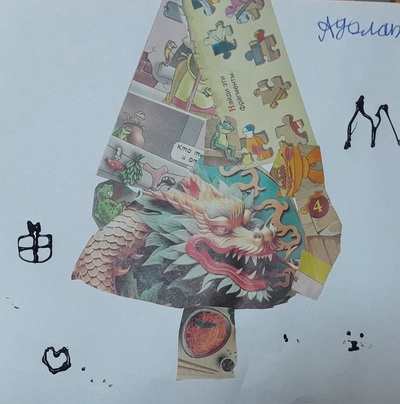

- Kids were working, cutting out their pieces and composing their collages. They were also looking for pieces for their friends. All this time we were having an open class dicussion about different artistic decisions and the bits and pieces that match or do not match the individual collages.

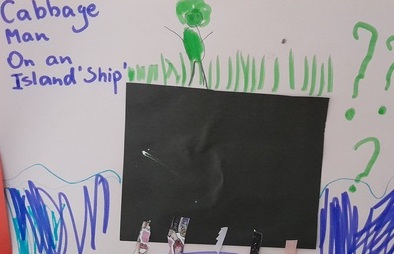

- In the end, we briefly demonstrated all the trees, together with the title.

- In order to create a more festive atmosphere, I put on some non-invasive instrumental music, Christmas-themed.

Why we like it

- The collage was a success. The students got really involved perhaps because the activity gave them an opportunity to be creative without requiring any real artistic skills, drawing, sketching or painting which sometimes can be a challenge.

- It took a while for the students to choose the theme but it is perfectly natural because they needed time to leaf through, to see what is available and to make up their mind and to select something. But I was really happy because it was clear and obvious that they really did make a decision and focused on the colour, one specific item or a general idea to represent. What’s more, I could see that the kids themselves were happy and proud of their choices especially when their pieces were completed.

- The task became a collaborative one although only by accident. Once it became obvious what everyone was working on, we all started to suggest and to offer pieces that we found in the journals that we were looking for. ‘I’ve got a yellow sofa here. Do you want it?’, ‘There is a princess here. Does anyone need it?’ and so on. It started with the teacher but the kids picked up on it. It is definitely something that I will be introducing purposefully the next time we do a collage.

- We used the A3 paper but the A4 sheets are also an option and the trees will be easier to fill in as the smaller the paper, the fewer the elements.

- We started with drawing the triangle on the A3 paper and went on to fill it in with the items. Two of my students did not have enough time (and the chosen elements) to complete the tree in one lesson. We are going to finish next week, we have this opportunity. However, that made me think that it might be a good idea to choose a topic, cut out all the elements and them compile them into a tree, making a conscious decision regarding the size of the tree and opting for a smaller version if time or resources are limited.

- I presented the idea of a combined technique: a collage and drawing, to fill up the space with own drawings, if needs be, but, in the end, not one of my students decided to use this option this time.

- The decision to put the background music on was a good one, too. It helped to create the atmosphere and, after a while, kids asked for the permission to put on their favourite songs which was granted and we ended up working and singing together.

- As regards the language production, a lot was going on because we were chatting throughout the lesson but I have to be honest about one thing – my older group are already a high level, some of them very close to fully communicative in English and even bilingual. That is why I didn’t need to do much to encourage production in the way an EFL teacher would. They wanted to talk and we did, in English. However, there are other options for the lower level and the EFL/ ESL students. I am still to try these in class but off the top of my head, I would go for:presenting the collage with the title, calling out the names of all the elements of the tree (or as many as possible), choosing the character who might like this kind of a tree. I am quite likely to teach the same lesson on Monday next week and, if I do, I will be updating the post soon.

- We did it in our Art classes but it might be a fun activity for a regular VYL or YL class, perhaps even with teenagers.

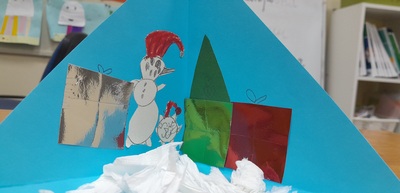

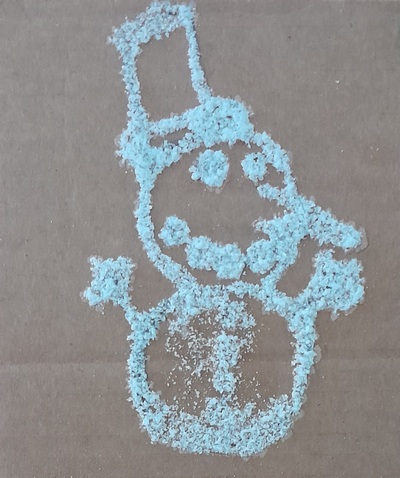

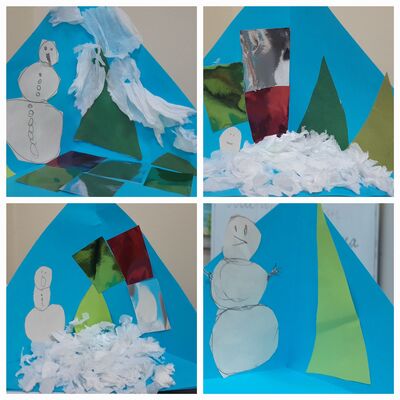

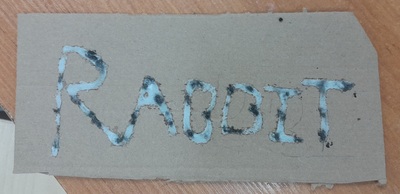

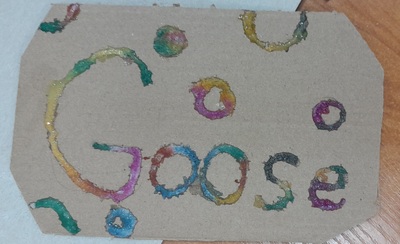

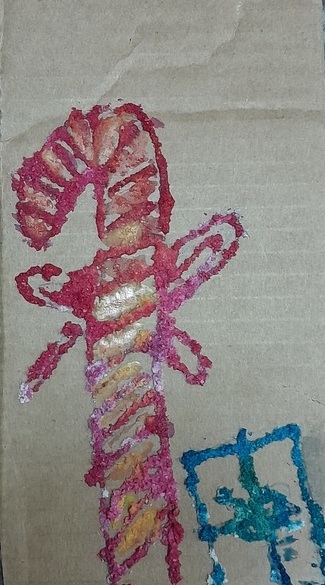

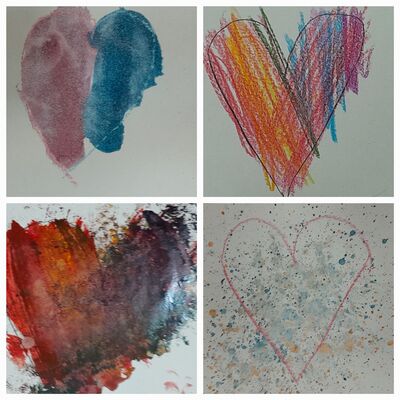

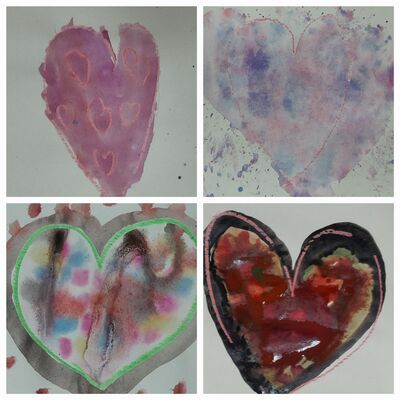

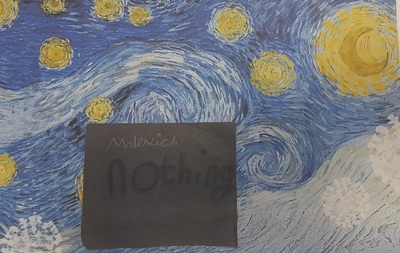

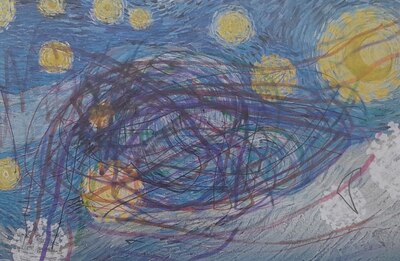

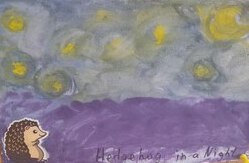

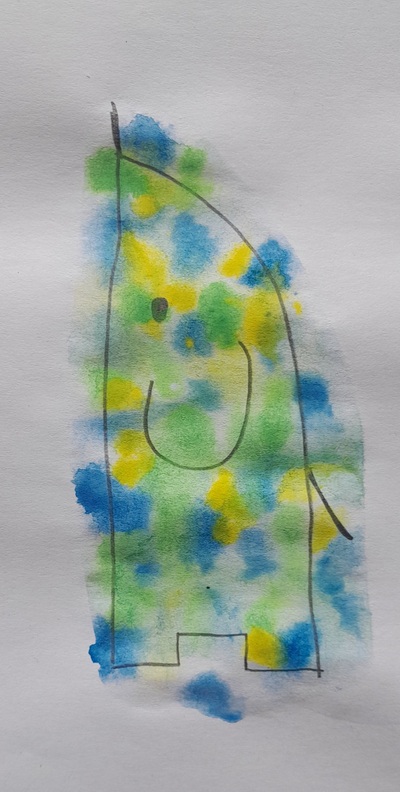

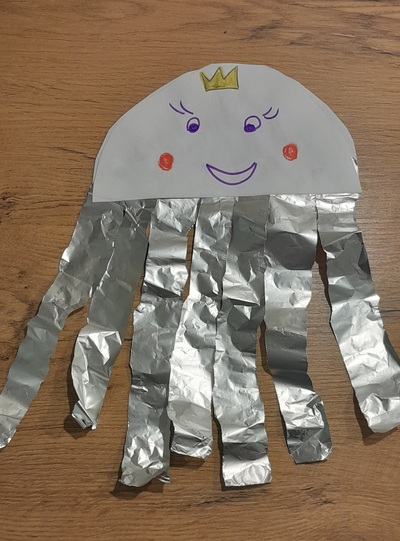

Here are some of the Christmas trees my students created:

Happy teaching!