PEPELT or Picturebooks in European Primary English Language Teaching

Fine Art Coloring Pages with ideas for Art

Teaching English to Kids

PEPELT or Picturebooks in European Primary English Language Teaching

Fine Art Coloring Pages with ideas for Art

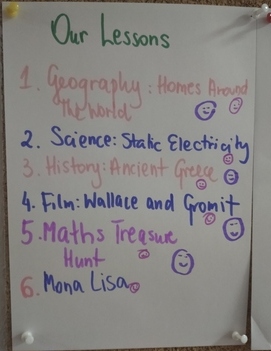

‘Anka, what about the pirates?’ was the thing I heard on Tuesday. The sentence was uttered in the middle of the lesson, in absolutely no relation to anything that happened, apart from the fact that the theme of the unit is the sailors, the mysteries of the sea, The Mary Celeste and I may have, at one point, mentioned pirates in passing. They did notice (of course), they did remember (naturally) and they waited for the best moment to use it against me. Obviously.

The funniest thing about it was the tone of voice that my kids used in that kind of situations and it is probably one of the things that I should add to the list of all the outcomes and consequences of working with a group for a prolonged period of time (you can find the post here). This tone of voice is a wonderful mix of a gentle scorn, a genuine inquiry, an honest plead and a teeny tiny layer of sarcasm. My kids are so good at it that they can squeeze it all in one word. Sometimes they just say ‘Anka‘ and it says it all…

Anyway, we did the Pirate Lesson, all the details and materials below. Enjoy!

Ingredients

Procedures

Why we liked it

Happy teaching!

Ingredients

Procedure

Why we like it

Happy teaching!

This post, like many others, starts in the classroom…

The thought falls on my head out of nowhere.

We are playing the game with the first conditional. There are only four of them, on the day, in-between the holidays, so we don’t even bother to go into the breakout rooms, we are playing together. It is not even a real game, either. Someone starts a sentence, someone else, called out, thinks of an ending, action – reaction, a situation – consequences. And they are just producing. Coming up with great ideas, some of the sentences just down to earth and realistic, some of them, as we call them, ‘creative’, just for laughs. And so we laugh out loud. A trainer in me suddenly realises that the lesson plan (if there had been a formal lesson plan) should include not only the traditional elements, like the staging and ‘the teacher will’ and ‘the students will’. The trainer in me realised that it might be worth considering to include a laughing fit and the necessary calming down part in the timing, in the assumptions and the potential problems and solutions…We laugh a lot with my kids.

Unavoidably, I realise, I get those constant flashbacks, those mini-trips into the past and I am looking at my students, today already 10 and 9 (or 8 and 7, still, some of them) and I remember how we walked into the classroom together, for the first time, me on my toes, all eyes, all ears, and them cautiously taking every step and every action. I do remember how we learned to say ‘Hello’ for the first time with some of them and how we first said that we don’t like broccoli ice-cream (except for Nadia, my little rebel). How I used to need lots of miming and scaffolding and modelling, with every single activity and how they’d start with single words, then move to phrases and to sentences.

And I, who was present, 99% of the time, over those seven years, I cannot believe my own eyes and my own ears now, how they throw the language at me, storytelling, or using the Present Perfect in free speech. Or the first conditional.

What does it mean for a teacher to continue for an extended period of time? What does it mean for the business? How does the methodology change? Does it change at all? What do the parents think? And, last but not least, perhaps it would be better to change the teacher once in a while?

This post will be very personal. This post will be very emotional. But I would like to look at it from the other points of view, too, thinking like a trainer, thinking like a methodology expert and, also, inevitably, thinking like a teacher and like a human, too.

In order to make it a bit more objective and more like a research, I asked my teacher friends for help. This post was written with the help, support and contributions from my amazing colleagues: Ekaterina Balaganskaya, Nadezhda Bukina, Marina Borisova and Tatiana Kistanova. Thank you!!!

Are you still up for such an adventure? Follow me.

Over to…a teacher trainer

Over to… a teacher

Over to…a human

‘If you meet with the same people twice a week for 8 – 10 years, you can’t help loving them‘ (Marina)

‘It’s a joy to see them grow, to see the progress and the results. Develop relationships and see them enter a new age group‘ (Nadezhda)

‘The best thing about it was that I knew them and they knew me, the rapport was strong‘ (Tatiana)

‘When I was moving a country, they were devastated. Luckily, we could continue our lessons online‘ (Ekaterina)

A change would do you good? The other side of the coin

Because, of course, there is one! Changing the teacher might be beneficial! On the one hand, as Nadezhda mentioned, the teachers themselves might feel the impact of the long-term interaction, some form of material fatigue, and in such a case a change is more than welcome. In such cases a change of a teacher might be the solution. A new teacher means new methods, new approaches, a different sense of humour…

Sometimes this ‘tiredness’ and the call for a change may come from the fact that students are growing and transitioning into another age group and the students might welcome a more official confirmation or recognition of that process. Perhaps, the change of a teacher might do the job here. If, for example, it is Mr Alexander is the teenage groups’ teacher then him taking over the group from taught so far by Miss Carolina is going to be some form of a rite of passage.

However, it needs to be mentioned, it is not as straightforward as it might seem. First and foremost, the students may not want to change the teacher at all and, in such cases, it is enough to tweak the format or the routine a bit. Then it might be that the outside circumstances change and they sort the problem out. Ekaterina shared her story of one of her groups with whom she started to consider the possible change of a teacher as the kids’ growing up and changing into teenagers resulted in some discipline issues and, as a result, the lessons not being as effective as they previously had been. However, here, the problem sorted itself out – due to the pandemic the class was transferred online and it turned out that the physical separatation (or the space and the own territory that the students gained) was the only thing that the group needed. They still continue with Ekaterina as their teacher.

This brought my own group to mind. The kids were still in pre-school, year 3, when we were asked to give our cosy kiddies classroom to a younger group. We moved and the most surprising thing was that it turned out to be an important stepping stone for the students. ‘We are real students now!’, they kept repeating and back then I was just listening to them and giggling inside that the big desks and big chairs can make anyone so excited. Today, when I look back at it, it seems to be this perfect moment in the life of a group when a change was needed. And it did take place, although, yes, without changing the teacher.

The most important thing to consider here is how the students can benefit from the new circumstances. Marina brought it up, too and, Ekaterina gave a perfect example from the British schools. In the schools her children attend, there is an obligatory change of a teacher every year, with Miss Elena only teaching the 4th-grades, Mr Peter only working with the 6th graders and so on. The system was introduced in the school to ensure fairness. This way, all the children get a change to work with all the teachers throughout their school life and the is no chance that, due to some ‘preferences’, class 4A only gets ‘the best teachers’. Not to mention that this must contribute a lot to bonding and building of the community as little Pasha will know all the teachers personally and all the teachers, after a while, will have had Pasha in their classrooms.

The end is the beginning is the end…

The most interesting thing is that, from among the teachers who waved back at me and wanted to chat about the long-term teaching of a group, there was nobody who would be a strong proponent of the Change the Teacher Every Year approach. Can it be considered a sign? I have no idea but, if, by any chance, there is anyone among my readers who has had an experience with it, please, pretty please, get in touch, I would love to talk to you!

Happy teaching!

A lesson is like…

There is nothing like a good metaphor and I use it a lot in the classroom, to give feedback to my students (‘Your essay is a bit like a skeleton, all the good bones but no muscles at all’), to explain grammar (‘Reported speech is basically telling stories’) or to manage the behaviour of my younger students (‘This desk, Sasha, is like your island and these other desks are other island. We don’t travel there. Never ever ever!’).

I also started to use metaphors in teacher training and, of course, you can read about it here and here and this is how this post started, too.

I asked my trainees ones how they would describe a lesson in terms of a metaphor and I found out that a lesson is a lot like: playing football, playing a game of snakes and ladders, a journey, a frame…I am getting goosebumps now because I know that there WILL BE a separate post about that, soon.

A lesson is like a story

Oh yes, it is! In a good story you absolutely need a good opening line (this is how I choose my books, yes. Because if the author did not bother to make an effort to say hello properly, why would we even be talking, eh?), a set of interesting characters, some adventures, some challenges and achievements, a climax and the ending.

In terms of a lesson, these would stand for a warmer activity (a good opening line), the community of the teacher and the students (yes, we are the characters), some engaging activities (our adventures), some new things, some learning and development (or the challenges and the achievements), one amazing focused task because all the roads lead to Rome (and this is our methodological climax) and….a good cool-down activity aka the ending.

We absolutely need the ending!

First and foremost, a lesson needs an official round-up, the final touch, the coda, the summary of everything that has happened during the lesson. Since one does not walk into the classroom and start the lesson without saying ‘Hello’, nor does one leave without saying ‘Goodbye’, there should be the first real activity of the lesson and the last real activity, too.

What’s more, a good ending of a lesson is also an introduction to the following one. If the lesson finishes on a high note, the students will leave the room looking forward to coming back next time.

# 1 Finishing with a song

An easy and no-prep resource, especially with the younger students. A song is a signal for the students that we are finishing but it can be also a signal for the parents waiting in the hallway. It can be the same good-bye song in every lesson but it can be a song that the students choose to finish the lesson with. This is an especially useful trick with the older and more advanced children, who might eventually get bored with the same song. With one of my online students we had a tradition of choosing one of her favourite songs, in Russian, to listen to and to dance, after the offcial lesson time, just as this thing that we did together (and I had a longer break in-between classes and I could spare a few minutes). One of my trainees, Nathalie (lots of virtual hugs here), also built in a dance into her class routine. At the end of the lesson, the kids would choose one of the Super Simple Songs, for example, get up, find a place in the middle of the classroom and just dance and sing, together with the teacher and then go home.

I have yet to start experimenting with songs with my older students.

# 2 Finishing with a story

Admittedly, that is a part of the routine that is something of a staple food in my pre-school and primary school EFL lessons. Stories, both storybooks or videos, can be used either to revise the key language or to introduce and practise the new language, not quite related to the topic of the lesson. From the point of the view of the lesson, the story is a part of the ritual and something that helps to build the class community.

In the classroom, we clean up after the focused task, set homework and go back to the carpet (preschoolers) or to our hello circle (primary), we choose a story and read or watch it and talk about it. Then, the only thing left is the goodbye-song. And stickers).

This is, probably, one of my favourite ways of finishing a lesson, because we get a chance to settle, to bond, to practise the language and to express opinion, all in one. I am wondering whether and how my older students could benefit from these, too. Something to experiment with in the next academic year, perhaps?

# 3 Finishing with a feedback session

There are many ways of organising a feedback session after the lesson, depending on the aim of the feedback session.

It is up to the teacher to decide how frequently any kind of feedback can be carried out: once a week, once a month, after each test or after any lesson with a new element in it such as a new activity or a new game.

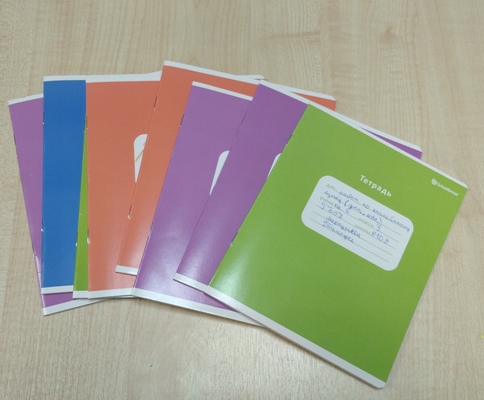

# 4 Finishing with a self-reflection task

This activity is an extension of the previous point but it focuses more specifically on the content and, even more specifically, on the vocabulary. My students (primary and teens) had their notebooks which we used for taking notes and for the self-reflection tasks, too.

At the end of the vocabulary lesson, the kids take their notebooks and look back at the lesson and categorise the words according to a number of the following categories: the difficult words, the easy words, the useful words, the words that look strange, the words that sound strange, the words that may not be very useful…

They can either create their own lists by copying the items from the board or the coursebook and by categorising or colour-coding them. A short speaking activity would follow in which the students explain their choices to their partners in pairs or small teams.

# 5 A revision task

That is another set of tasks that we sometimes use also based on the key vocabulary in each particular lesson and it has got a lot to do with everything that is written on the board already such as the new language or the emergent langauge. The main aim here is to give the students one more opportunity to use the target language. Since these games have no definite ending, their length can be adapted to the amount time left in the lesson.

The students work in pairs and can play one of the following games:

Sometimes we also play the memory game with the whole class: the students take turns to close their eyes, the teacher erases one or two items, the students open their eyes and try to recall the words that have disappeared as well as all the other words and phrases from the previous rounds. The class listen and help out with definitions and associations. The bonus? The board gets cleaned))

# 6 Finishing with an introduction to the following lesson

This approach to the finishing the lesson was the result of the reality of the teaching life. No matter how well you plan your lessons and how many optional activities you have up your sleeve, it might still happen that everything has been done and there is still some time left but not enough time for the teacher to properly spread the wings, be it in a game or in any other fully-fledged task.

In such a case, it might be a good idea to introduce the topic of the following lesson, without properly setting the context (no, time, remember?) for example by:

This will create a link between the lessons and it can be further extended by a homework along the lines of: ‘Find out more about…’. All of these can be easily adapted to almost any topic.

# 7 Finishing with a game

The games chosen to finish the lesson with should be fun (the students are already tired and less able to focus), fast (if there is a lot of time left, perhaps it should be devoted to something else) and offering some flexibility to the teacher (aka games with no definite end or result that can be stopped or paused at any given point).

We like to play:

In order to better manage the game and time in class, we started to play these with the same teams over a series of lessons, pausing when it is time to go home and recommencing in the following lesson.

Bonus: An Art Project

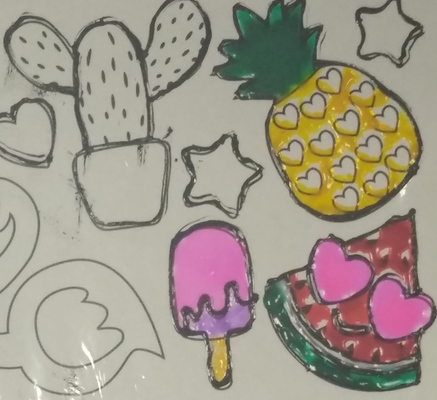

‘Anka, what’s this?’ the kids asked when entering the classroom and noticing a few boxes of the stainglass paints.

‘These are special paints. We used them to make these special pictures with the little kids.’

‘Anka!’ they said, in that very special tone of voice that my kids have mastered, the voice reserved for these particular occasions, to compain, to chide and to express disappointment. ‘The little kids? And what about us?’

So I had to think of a way of including this particular project in our classes. Making stained glass pictures is one of the coolest activities ever but it takes time as the various layers need to get dry before you apply the following ones and there is virtually no chance of completing a task in one lesson. Not to mention that it is a perfect decorative kind of a craft and trying to adapt it in order to maximise production would be simply counterproductive.

Instead, I wrote to the parents and I explained that, instead of a game, at the end of the lesson, for the next few lessons, we would be preparing our own stained glass pictures. The kids chose a template or designed their own pictures, they drew the outlines, they coloured them in and, as soon as they were ready, they took them home to cut out and to display them. All in all, it took about 5 minutes over a series of four lessons.

Bonus: The Chameleon Day aka Google Search

Choosing virtual stickers is not a new idea and thanks to Miro we have lots and lots of fun and we can keep track of all of our stickers throughout the entire year, if necessary. Here you can read how we deal with that with my primary students.

Further reading

The 9 Best Ways to Finish EFL Lessons from the ELT Guide

End of Lesson Activities for ESL Classes from English Teaching 101

7 Best Ways to End a Lesson from Busy Teacher

How to Finish Your Lesson Effectively from The TEFL Academy

15 Awesome Wrap-up Activities For Students from Class Craft

Happy teaching!

*) This material was collected and put together for the online training session organised by National Geographic Learning for Russia in October 2021 where I had the privilege of sharing the zoom stage with Dr Joan Kang Sheen and Tatiana Fenstein.

Ingredients

Procedures

Why we like it

Happy teaching!

Ingredients

Procedures

Why we like it

Happy teaching!

It was a typical day in the life of a small scale Mary Poppins. I set out for a shift at the volunteering centre and, as an experienced one, I could not imagine to go unprepared, even if minimally. I thought that, at the very least, we can do some circle magic. I could not take everything but I had a big pocket and so it got filled in with three glue sticks, an envelope full of circles, a small packet of colourful feathers (that was a nice coincidence that I had it). A4 paper and a box of markers did not fit in one hoodie pocket.

When I arrived and started the shift, it became obvious very very quickly that the place is not ready for any craft activities because, apart from one small table and a few little stools and a box of coloured pencils, there was nothing. Or, rather, there was only me and my pocket.

There is some beauty in that, really, when you get to see how your brain starts to get involved in order to think of a solution. Sure, THAT was not about sending a man to the moon or putting together a new recipe, but, still. I was building a grid for our version of hop-scotch and sorting out toys, and the brain was trying to imagine what I can make out of the contents of my pocket. A little chick, that’s what.

Ingredients

Procedure

Why we like it

Here are some other circle-based craft ideas

Here are my own Frogs Etc, my snowman, and all the circle ideas.

Here is a lovely bear craft, here a ladybird craft, and here a caterpillar, too and here, a bunch of other activities, probably too complex for the EFL classroom but definitely worth looking at.

Masking tape aka Painter’s tape

The funny thing is that I cannot remember when I discovered that the painter’s tape existed. Maybe it was Vita, my friend and my colleague who first brought it to school…

What I know is that for the past four years I have always had a roll of two at home and a roll or two at school. Because, right now, there is no classroom without the painter’s tape.

Every single time we do anything in the hallway, any kind of a treasure hunt, any jigsaw puzzle, anything which involves things being put up on the walls, the painters’ tape enters the picture. I prefer it to blutack because I don’t mind just throwing it out (instead of peeling it off carefully from every single scrap of paper) and, even more importantly, my students don’t feel tempted to nick the tiny little bits of the precious resource.

My primary students who are learning to read and write know this resource very very well. We use the tape to write instructions for different activities, especially if they needed to be displayed around the school and all our lessons would start with a fun activity with the little chairs – some of them would have the bits of the tape with funny words on them, for example choosing the place to sit (‘I am sitting on the Happy Octopus’), making sentences with the key word written on the chair (‘dancing’ – ‘Today I am a dancing hippo’) or even writing and creating random combinations of words.

Apart from that, pieces of the tape can be left on each table, one per student. They can be used in any kind of surveys (‘Which game would you like to play?’, ‘What was the most difficult part of the lesson?’) but I also noticed that the students liked to write on them, just to express themselves, to scribble while they were listening or to just to somehow personalise the table where they were sitting.

The tape can also be used to help group and pair the students. There should be a piece of tape on every desk and on these the teacher write the names of different superheroes (a very broad term in my lessons, it can include both Batman and Cheburashka, Harry Potter and Aleksander Sergeevich Pushkin, Lionel Messi and Santa). On entering the classroom at the beginning of the lesson, the students pick out one of the cards with the same name from the teacher and this is how they find out where they are sitting on the day. The same cards can be used later on to mix the students, with the teacher (or one of the students) picking out two cards to decide that in the following activity Superman will be working with Harry Potter and Robinson Cruzoe with Superman etc.

AND, though there are no photos, the painter’s tape was THE LINE on the carpet that helped my little babies sit in a safe and appropriate distance from the big TV on the floor.

Last but not least, we have used it to create a city plan on the floor which we later filled in with flashcards and we used to move around. It is a rather limited use, but, oh what an amazing lesson.

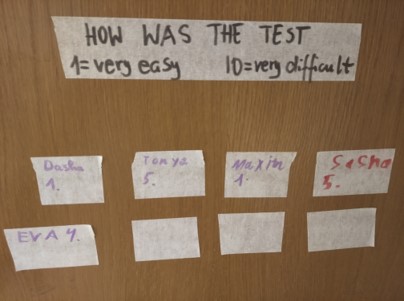

The door

The door is the most underestimated and underloved part of the classroom. And how undeservedly so! Even if you have only the most standard door (not those double door straight from a castle), that is a good two square meters of a notice board, ready to use! It would be recommended to check the material, the surface and the ‘stickability’ and to test different adhesive materials that will not destroy the door itself but there is scotch, there is the painter’s scotch and there is blutack to name at least a few that could be used here.

In my classrooms we have used the door in the following way: putting up the huge posters to use instead of the numbers (The Caterpillar Classroom, The Baby Shark Classroom, The Cookie Monster Classroom), putting up the homework poster (‘Did you do your homework?), putting up the washing line with all the clothes to use during (‘Today I am wearing…’), putting up the classroom rules posters, the library reviews poster (for the kids to leave the reviews after they have read something), the test feedback poster (‘How difficult was the test? 10 – very difficult, 1 – not difficult at all) and any class surveys completed on the way out, the sight words reading practice on the way in, displaying the alphabet poster when we were just starting to read, displaying any of the work that the students produced (when the walls were already taken) and, last but not least, or quite the contrary: the first ever: The Door of Doom aka the poster we created with my FCE students by adding bits and pieces to the poster throughout the course. These bits and pieces were all the things we struggled with: the mean phrasal verbs, the less common suffixes, the collocations that we would always make a mistake with and so on.

Next time you are in the classroom, have a look at the door and at this whole unused space…And what you could do with it. Once you start, you will never stop.

Counting sticks

This entry is perhaps not such a great surprise. After all, all the little people (and their teachers and parents) are very familiar with these colourful plastic sticks. Everything else aside, this should be one reason to be including them in our EFL lessons.

We use them mostly to count, of course, the kids pick two or three or twenty and this helps to make such an abstact idea as numbers a little bit more visual (because three items lying on the table, three sticks, three fingers or three dots on the dice are a better representation of the secret that this symbol ‘3’ stands for) and kinesthetic when we let the kids manipulate the sticks. Luckily, the sticks are cheap and easy to get so having lots and lots of them, enough for everyone, is not a difficult aim to meet.

One of my favourite games to play (perhaps because it is a perfect solution for a lazy teacher) is using these together with the paper plates with numbers. The kids look at the number, count the sticks and add or take them away, in order to make sure that the number matches the number of sticks. Which is also the beginnig of adding and substracting.

By the way, flashcards will do here, too, but the plates have the advantage of having the rim and the sticks do not slide off and you can easily just pile them up on top of each other, put them aside and sort them out after the lesson.

With my ‘adult‘ pre-primary kids, we have used these same counting sticks to help children manage a pair-work activity, to add a visual and kinesthetic element to the verbal exchange. We were practising different varieties of ‘What’s your favourite…’. The kids were sitting in pairs, on the floor, around a set of flashcards that would symbolise the themes (an apple for ‘What’s your favourite fruit?’, a teddy for ‘What’s your favourite toy?’ and so on) and one student in each pair would get a set of five sticks. They were supposed to ask their partner five questions of their choice (we had ten categories) and while doing that, they were supposed to put the stick away, on the relevant card. We used a similiar tool when they were interviewing their partners about things they like (‘Do you like…’ + any words of the kids’ choice) and I guess it can be adopted to pretty much any structure.

Plastic cups

Or any other recycled cups (like those in the photo) which are easily available. They are my favourite resource to sort out materials (pencils, pens, bits and pieces for a craft activity, especially the leftovers, which I hide in the cupboard for later). They also help to organise materials which I give out to the kids, for example we have a set of boxes with crayons organised by the colour, for some, more teacher-centred activities, as here the teacher is the one in charge AND a set of cups organised in sets, one full set per student, which we use in all the SS-centred activities in which the students make decisions which colour to use.

With my older students, I use the plastic cups whenever we use dice in class (and that is OFTEN). The dice given to students (kids and teens) ‘just like that’ have the most amazing ability to fall off the tables about once per minute. Plus they make LOTS and LOTS of noise and if you have a group of then and five dice are rattling and rattling…Well, you can imagine. If you put each dice into a plastic cup, you can still shake it and get a number and everything is more manageable. I think I saw it first in Nataliya T’s class and here are my thankyous for this idea!

Paper plates

Oh the paper plates! They are of course used at parties and in craft lessons to make clocks, spinners, plates for all the ‘fruit salad’ craft activities, snowmen, frogs, chicks, rabbits and what not…But there is so much more!

For me it was this one day when I got an idea for a great lesson for which I really needed the number flashcards. These, however, were left behind in the office, so getting them for the lesson that was the first lesson of the day, early in the morning was out of the question. I rushed to the school cupboard in the house, to go over all the treasures there, with the idea of something that could help me replace the flashcards and there they were – a set of colourful cardboard plates from my local supermarket (which I must have bought for some class party earlier). Creating the flashcards took three minutes and a permanent market and it turned out that these particular plates (many of which I bought later on in the same supermarket) were perfect for it: big, durable, colourful but not too colourful since there was a thick colourful rim but the centre was just white and empty aka perfect for writing!

We normally use the number plates like any other flascards, first and foremost but the different shape adds to the variety and makes the topic of numbers a bit more fun. We also use them together with the counting sticks (see above) or with any other bits. We used the numbers 1 – 12 to create a huge clock on the floor and we played some movement games with it.

The plates became the canvas that helped me create my amazing emotions and adjectives cards (sorry about blowing my own trumpet here but there is a lot of love here) which we have been using for more than two years now.

Not to mention that the plates can be a very useful tool to organise all the bits and pieces while getting ready for a craft activity, hats for the snowman on one plate, scarves for the snowman on another, and they all can be stuck on top of each other. And, as you know, every little helps to make the teacher’s life a bit easier.

What are the unsung heroes of your classroom? Please share!

Happy teaching!

Ingredients

Procedures

All the variants (so far)

Why we like it

To be continued. Soon. We are quite likely to get very bored with what we are doing at the moment…

Happy teaching!

*) My favourite so far! It is amazing how my students come up with their own metaphors and associations, both the teenage group and the kids. Here are a few quotes: ‘I felt like Chebourashka because I was a bit confused’, ‘I feel like Robinson Cruzoe because I am locked up at home now’, ‘I feel like Masha from Masha and Medved because I am a bit crazy today’, ‘I felt like Santa because it was my friend’s birthday and I had a present for him’, ‘I feel like Superman because I did all my homework really fast’…