Dear Mr Bruner,

I am happy to inform you that, inspired by your article, I have decided to follow your example and to start experimenting in the area of scaffolding…

Oh, how I wish I could write a letter of that kind. Since I first read the article by Bruner, Woods and Ross on the original research and how the term ‘scaffolding’ started to mean what it does to us, teachers and educators, it has become a kind of a life mission to spread the word about it among my teachers and trainees, conference attendees and, of course, the readers of my blog. This is also the area that I choose to invesitage in my first classroom research project as part of my MA programme.

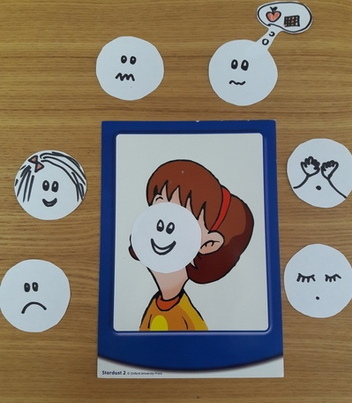

Of course, the most important things keep happening in the classroom, in the everyday when you observe and adapt your instructions, gestures, voice and actions to better suit the young or very young learners as regards demonstration, marking critical features, reduction in degrees of freedom, recruitment, direction maintenance and frustration control (the six orignal features outlined in the article).

This time, the starting point was the lazy teacher…

I started to plan the final lesson with my three pre-school groups that also happened to be our Christmas lesson. And it was out of this tiredness and the madness of the end of the year that made me wake up one day and decide: ‘I am going to repeat the lesson!’

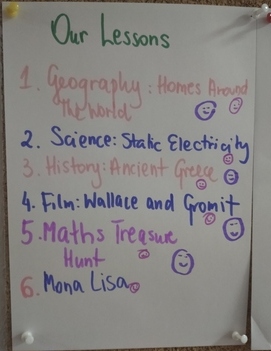

Three lessons in a row, three different levels, three different age groups and the same lesson plan. Well, to a point, of course. We would all study the same vocabulary set and sing the same songs, but the activities would vary, depending on what the children are capable of.

Topic, vocabulary and structure

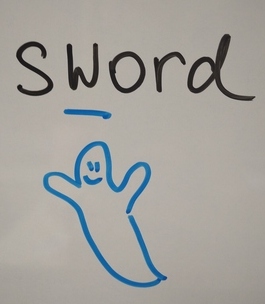

There were eight words in the set (Santa, a reindeer, a stocking, a Christmas tree, a present, a start, a snowflake, a snowman) and I wanted to combine them with the question that we all had been practising before: ‘What is it?’ ‘It’s a…’.

The level 1 kids (and the youngest group) have got as far recognising the words and pointing at the right flashcards and participating in the ‘What’s missing?’ game although most of the time they would guess the missing word in Russian and they actively produced only some of them in English, such as ‘a star’, ‘a snowman’ and Santa. We also watched the ‘Guess the word video‘ and it was a chance for us to drill the vocabulary in a different way. We also introduced ‘What do you want for Christmas‘ and it was a nice opportunity for us to revise toys which we covered in the previous unit. But only that. In the end of the lesson we also had time for storytelling and we used Rod Campbell ‘My presents’, again as a way of revising the key vocabulary.

With the level 2 kids, we did pretty much the same but the kids were able to remember and to reproduce all eight words really quickly. We played the same game (What’s missing) but they were all actively involved and producing. We watched the video and guessed the words, pretty much just the way the younger group did, although it was interesting that I did not need to encourage them to repeat the words and, as soon as the full picture and the correct answer was revealed, the kids said the word without any cues from me. It seems that due to their age and to the fact that they have been in class for longer, they are much better used to that kind of reaction to the content. We seem to have developed that habit already.

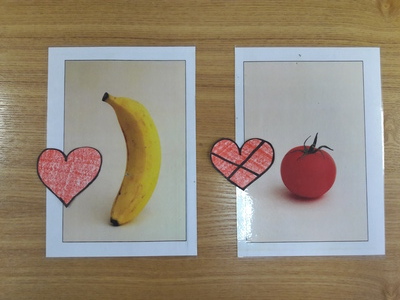

As for the song, we even managed to personalise the song and talk about whether each of the presents featuring in the song are a good idea (or not? ‘Not’, according to some students:-) and we sang a verse for each of the kids:

‘What do you want for Christmas, Christmas, Christmas? What do you want for Christmas? Santa is on his way…’

‘I want a…’

I did not use the storybook with the older children. I had planned it only for the little ones. For the older ones, we had a back-up of an episode of Christmas Peppa, but, in the end, there was no time for that.

The oldest group, level 3 kids, need only a quick revision of all the words and then we could play a variety of games. We did not even play ‘What’s missing?’ as they are too ‘adult’ and this particular game is not challeging for them anymore. Instead, we played a team game, ‘Tell me about it’, in which the players choose a box, open it and say something about the picture hidden in the box. And they collect the points.

We did use the video mentioned above but in this lesson it was not just a simple guessing game, we also managed to talk about whether each round is going to be easy or difficult and then to comment on what it really was. And, of course, the song was also personalised and followed-up by a proper chat. There was also another song, ‘Who took the cookie from the cookie jar?‘, in its life acquatic version (nothing to do with Christmas, but the kids were curious and this is the game we are playing right now). This group are already quite good at personalising songs (aka ‘The original version is good but let’s see what we can do with it and how can we make it better?’) so it was the kids to suggest that we start singing it when we pick up our surprise at the end of the lesson from the reception. If I rememeber correctly, the final version of it (as shaped up by the kids) went along the lines of: ‘Who took the surprise from the surprise jar?‘

I was teaching, having fun and keeping my eyes and ears open and trying to remember what was happening. It was already very interesting but I was really waiting for the most important part, the cherry on the cake.

The cherry on the cake

Surprisingly enough, this time round, it did take a long while to choose the craft activity but finally I settled on the snowman. I found something that I liked among the 25 Easy Snowman Crafts For Kids on countryliving.com. I planned the lesson, spent an hour cutting out the circles, the noses, the hats, the arms and the Christmas trees and orgnising the room. And then we took off.

It so does happen that although my children are divided into groups by the level and by the age, there are exceptions and special cases in all three groups.

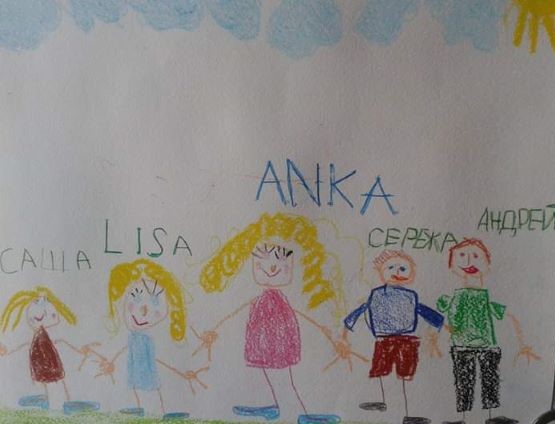

The actitivity, the materials, the staging and the instructions were exactly the same in all three groups but the outcomes (visible in the photographs below) and the scaffolding necessary (not visible in the photographs:-) heavily depended on the age of the students.

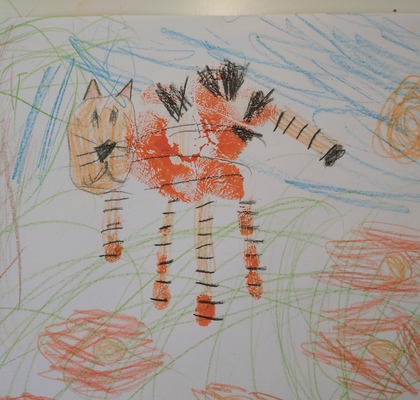

The youngest students produced these beauties:

This was interesting, especially because this lesson came first and after a very short moment, I realised that, while preparing and planning, I gauged myself for a slightly older audience and I had to adapt on the go, especially for the almost 3 y.o. girl for whom it was the trial lesson and the first 45 minutes in our classroom.

It turned out pretty quickly that it is quite a challenge to glue the ribbon, to turn the circle over and to tie it and that the orange ‘carrot’ nose is actually very small. But we managed, with the pace really, really slow and the teacher keeping an eye and demonstrating everything twice. Plus, yes, the teacher had no other choice but to help with the ribbon.

The age of the students shows most obviously in the way that all the small parts were glued and how the eyes, the smile and the buttons were drawn, with a different level of accuracy and precision. Almost where they should be:-)

And it was because it took longer to produce the snowman that I decided to skip the little sticky arms. They were too thin, too fiddly and too risky. And the snowmen still look pretty without them.

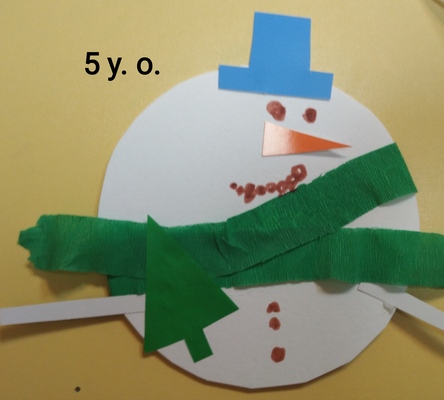

The snowman created by the 5 y.o. hands looks like that

First of all, the five-year-old snowmen did not take as much time to produce and the little fingers were much more agile and ready. As a result, the teacher did not need to help with the ribbons, the noses were handles with much more efficiency and we did have time to add the arms.

It is interesting to see that at this age, the students did observe the teacher (the mentor / the expert) to do exactly what she was doing but they were observing to figure out what had to be done and to interpret it in their own way. Some snowmen were happy but not all. Some had the scarf tied on the neck aka above the arms and the others had it more where their snowman-y waist would be. Some had the buttons and some did not. Some snowman mouths were a string of dots, some were drawn with a line. Some of the Christmas trees were glued on the snowman’s chest (like in the teacher’s model) but then again, some were holding them in their hands (although this obviously involves even a higher level of precision).

The 6 y.o. snowmen look like that:

The older snowmen are even ‘neater’ (in inverted commas here because I adore all of these snowmen, even the ones that look as if they were created by Pablo Picasso) and the evidence of precision and accuracy as well as even a more detailed and a more personalised version, which were the students’ own additions as they were not modelled by the teacher such as the eyebrows, the hat decorations (not featured in the photos) or a bigger number of buttons.

And the oldest of them all, the almost 7 y.o.

This snowman was made by our oldest student, a girl who is actually in school but who is finishing the level with us. As regards the level of English, the development of the literacy skills, she is like the other students in the group, but her motor skills are more developed and for that reason she usually is the fast-finisher. That is not an issue and while she is waiting for the group to finish, she usually continues working on her craft or handout, adding details and decorations.

This time round, she decided that her snowman is going to be a snowgirl, with her and a bow, which was her own original idea.

Reflections of a small scale Jerome Bruner…

This was an absolutely fascinating experience and I would really recommend it to teachers who work with different levels within the same age group, especially within primary and pre-primary where scaffolding seems to be one of the most important factors deciding about the task completion and success.

- It can be a great source of information, about the students’ skills and abilities…

- …as well as an opportunity to trial something new, be it a song, a video, a game or a craft activity and to learn more about this type of a task.

- It is a chance for the teacher to practise and to develp their scaffolding brain…

- …and a great opportunity for a freer practice in the area of differentiated learning, not only within the group of learners (something that happens in every class) but on the level of different age groups and levels

Like in the original experiment, the design or the choice of the task and the material is crucial but the holiday lessons, not really closely connected to the coursebook curriculum, seem to be a perfect way out.

What else? Not much? Some curiosity on the part of the teacher, some willingness to experiment and some flexibility in order to be able to adapt on the go. Plus, the eyes wide open to notice all the little changes and proceedings.

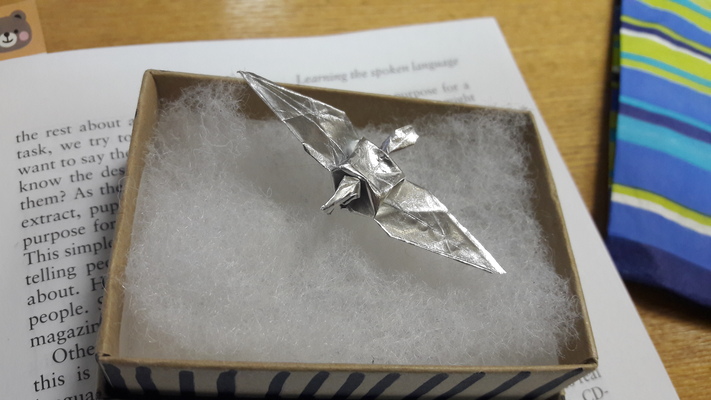

These two, in the photo below, are my own interpretation of the original craft and a more complex version of it, here in the form of a card, made by an adult (myself). Perhaps this is what I am going to make with my oldest primary group in our Christmas lesson. If we do, I will let you know how it goes. That would be, indeed, a nice follow-up and an extension of our experiments. We’ll see. In the meantime:

Merry Christmas! Happy New Year!

Happy teaching!