Once upon a time, there was a world in which children were developing their reading skills, imagination and creativity with storybooks read by mum at bedtime.

Then, the Wicked Witch of the West came and replaced all the books with apps, tablets and games. The Wicked Witch of the West said that it is all easy, available, accessible. All the parents and all the teachers applauded. The books lay forgotten and deteriorating, and a few years later, the time came when one of the dinosaur teachers by accident said ‘open your books’ in class and a little Masha raised her hand in the first row to ask ‘What is a book, Miss?’

Luckily, we are not there yet and, hopefully, we will never be. Of course, the pandemic was / is / has been a huge challenge for us in that department but, nonetheless, I do continue to stand proud in defence of paper and in defence of magic.

May this very post to be the introduction and the directory to everything that using storybooks in the classroom can be.

One thing that it definitely is not, is just opening the storybook and reading it out loud. This is what it can be.

One. Baby steps

At the start of the level 1 of any pre-primary or primary course, the kids are real beginners, they have no language, no structures and no vocabulary. It would be rather optimistic to hope that a teacher is going to be able to use a story with all its richness. However, that is also not a reason NOT to include them in your lesson plans. After all, storybooks are something that the little kids are familiar with, they know what dealing with them involves and that they are part of life. For that reason, they can and they should be used with children.

- Simple vocabulary revision with a different tool: the teacher points out at pictures in the book and calls out the colours, counts them, asks if they are big or small, if the children are happy or sad, if the students already know this vocabulary. This might happen only at the level of the colour (It’s green) and not necessarily with the actual noun (It’s a green fish), although, admittedly, there is some potential here, too, to learn the new vocabulary through storybooks

- Simple functional language practice: Hello Pete, Goodbye Pete in the first lessons with the book and then according to what the students know.

- Storybook reading-related language: something that will be introduced gradually but that will come in handy throughout the course, for example ‘It’s story time!’, ‘Sit down’ ‘Are you ready?’ ‘Turn the page’ ‘Do you like the story?’

Two. Role-play

This way of using a storybook will involve the students a little bit more as they will be retelling the story together with the teacher, as soon as they become more familiar with it. Naturally, not all the stories will lend themselves to this activity, only those that include some repetitive language, even if it is only one phrase. Stories that can be used here can involve

- Dear Zoo (‘I wrote to the zoo to send me a pet’)

- Where’s my baby? (‘Is this your baby, Mrs Monster?’)

- We’re going on the bear hunt (‘We’re going on a bear hunt, we’re gonna catch a big one. Oh, what a beautiful day. We’re not scared’)

- Any other story in which you might want to implement a structure that the kids might already know or that they might benefit from knowing, even if, originally, it is not in the story. For example, ‘…., Senor Croc’ is a storybook for kids in Spanish about the birthday party of the main character Mr Croc, by introducing the following ‘Let’s’ (Let’s open the presents, Let’s dance, Let’s eat the cake)

Three. Vocabulary practice

The storybooks are there and we can use them and the beautiful story and illustrations in any way we want. The story is not really read but told, with the language graded to the level and needs of the particular group.

Most frequently I choose the storybooks to go with the vocabulary that study in the unit. This way, the children can participate in telling the story and continue working on the vocabulary that they are learning. It will start with producing single words but it can lead to producing

- How to lose a lemur – to teach and revise transport

- Dear Zoo – to teach and revise animals

- Julia Donaldson’s The Smartest Giant in Town – to teach and practise clothes

- Go Away Big Green Monster – to teach and revise body parts

- Marvin Gets Mad – to teach and revise emotions and verbs

Four. More vocabulary practice

Taking one more step in that direction, any storybook can be used to teach, to revise and to practise any vocabulary, even if it does not feature explicitly in the storybook.

The first storybook that I have used in that way was the traditional story ‘The Three Goats Gruff’. The story is lovely all by itself but I have been using it to practise and to revise the food vocabulary. Only in my version of the story, every time one of the goats tries to cross the bridge and the troll attempts to eat it, they always have some food on them and they try to buy themselves out by asking ‘Troll, do you like bananas?’, which, of course, the troll never accepts.

Five. Storytelling without storybooks?

Absolutely! For example, because you realise that your own precious copy of Dear Zoo has been misplaced / lost / stolen only a few minutes before the lesson in which you want to use it…You do not give up, naturally, you only wander around the school, find a few flashcards and a box. As an experience it is unpleasant and stressful but, in the end, you realise that, hey, a storybook itself is just a tool and a story can be told without it. And it is lots of fun.

Another sources of inspiration for that kind of approach to storytelling, can be a series of storytelling videos produced in the 90s by the Brazilian TV Cultura. This example here is in Portuguese is a story about a crocodile, a grasshopper and a spider, with a scotch dispenser starring as the spider, a pair of scissors as the crocodile and a table tennis ball as grasshopper.

This kind of pretend-play with the use of the everyday objects or toys is something that children do in L1 as well and it can easily be implemented in our EFL lessons, too.

Six. I can read!

This is a big moment for the teacher and the student when they can finally take an active part in the proper reading of the story. For that reason, the storybook should be carefully chosen.

- ‘Bear on a bike’ is easy enough because the whole story is told through illustrations and single words or short phrases, some of which are also repeated. ‘Apple, pear, orange, bear’ follows a similar pattern

- ‘Llama, llama, red pajama’ includes rhymes and some parts of it are easy enough for the primary beginner students to deal with

- Graded readers and phonics stories that were specifically created for beginner readers

Seven. Storybooks for everyone!

A few years ago, at the IH YL Conference in Rome, Beverly Whithall from IH Braga gave a fantastic seminar on using storybooks with teenagers and adults. The older students, because of their maturity and the level English, can properly appreciate the story, its language, plot and illustrations and every story can be a starting point to a discussion. Just imagine a typical literature lesson that you had in school, when you are looking not only at the story itself but also at the bigger picture. Seen from that angle

- Rhinos Don’t Eat Pancakes is really a story about a family and about loneliness

- Elmer is a one big question of whether one should be like the everyone else

- Giraffes Can’t Dance is about bullying

- Up and Down is whether we should always follow our dreams

Questions

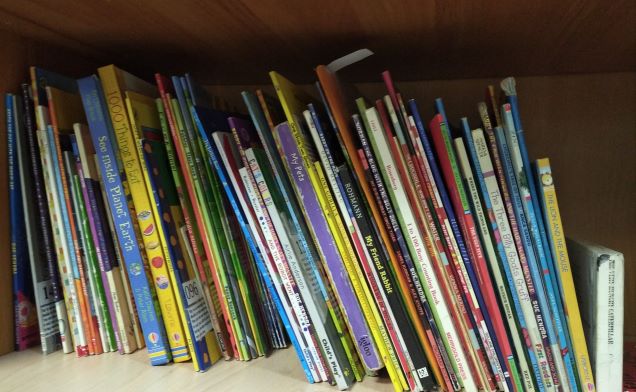

- How to choose a storybook? It might be a good idea to start with the classics but also to keep your eyes open while visiting bookshops and browsing, to find out more about the beautiful world of the storybooks and to learn more about how they can be used in the lesson.

- How long can I use the same storybook? Well, definitely more than once and as long as the students are interested. It might be a good idea to put the book away for some time and then return to it, letting the students choose which book they want to read or ‘read’

- How do I adapt the language? Like with all the lesson planning, for any kind of an activity, choose the aim first (functional language, structures, vocabulary practice, revision or introduction) and them adapt the book to help you meet that aim. The gestures, the visuals, the voice and the universal story magic will help children to understand. Translation will not be necessary.

- Do I need to include storybooks in every lesson? It is not absolutely necessary, it is like the other tools and techniques, they are definitely beneficial for the children but there is no absolute must to have them in every lesson. More likely than not, with time, you will see the positive impact of storytelling on the students, on the classroom management and on yourself and it is for that reason that you will want to include them in every lesson or almost in every lesson.

- How do I start? Slowly! Practice makes perfect.

Tips and techniques

- Let the children look at the story, all or some of the pictures, before you start telling the story, unless, of course, there is some big surprise in the end which should not be revealed too soon.

- This demonstration can be done in silence or the teacher can point at certain pictures and elicit the words from the students.

- While telling the story, point at the crucial elements in the illustration and pause to elicit the language from the children.

- If the kids are already familiar with the story, start telling it with mistakes and wait for the children to correct you. They are going to love it.

- Include gestures and physical actions that will accompany your story. This will help children first to understand the story and then to retell it and to really remember the language.

- If possible, use some prompts such as realia (toys, plastic food, clothes), flashcards or mini-flashcards.

- If possible, try to recreate the atmosphere of the story by preparing a soundtrack i.e. the jungle sounds for story set in the jungle, the beach sounds for the stories set by the sea etc.

- Don’t forget to use your voice, this is the teacher’s most important and powerful tool.

- Get ready and rehearse, think how you are going to position yourself, how you are going to hold the book, where the children are going to say.

- If you are not using the original story, try to remember what changes you have introduced in order to be able to retell the story in more or less the same way every time you are using it

- The storybook is never used in one lesson only. It is only in lesson two or three, when the students are already familiar with the story and with the language, that they can really enjoy it and participate in it fully.

Happy teaching!