When I look back at the two and a half years of the MA programme at the University of Leicester, I am thinking of a marathon (a prolonged period of strict routine, extensive emotional and physical expenditure and obligatory one-track-mindedness). Actually, five marathons in a row. But when I look back, it is also the time when one could revel in reading and research, having access to the treasures to the university libraries of the world.

Apart from going through piles of studies and articles to find out data for my assignments and thesis, I also started to make up a list of pieces to share with my teachers and my trainees. Jerome Bruner’s (et al) and the study of the role of tutoring aka scaffolding is already on the blog here and, I am happy to say, for a very long time, it was one of the most popular posts. It still stays somewhere in the top 15…

Today, part 2 of the same series. Enter: professor Marianne Nikolov.

A personal role model

There is something very touching about the career of professor Nikolov (PhD, Professor Emerita at the University of Pécs, Hungary), who after years and years of regular and everyday school teaching started to work as a researcher and, who, eventually, switched into the academia. This very research which is described in the article was her first long-term research, as she says herself, it is in many ways imperfect mainly due to the fact that it was carried out by someone who was, back then, an inexperienced researcher. So much more precious because of that and so much more inspiring for all of us, teachers and trainers, to get our own classroom projects started.

The presentation on the recent research into early years that professor Nikolov gave at the 1st Hellenic Conference on Early Language Learning in Greece, in 2013 is, in my humble opinion, a must for all the VYL teachers, as a crash course into the early years EFL.

‘Why do you learn English?’ ‘Because my teacher is short’

This gem, unique and unforgettable, is the title of the study that I would like to introduce you to and encourage you to read today. And, frankly, could there be a better title to an article devoted to early years and young EFL learners? I seriously doubt it.

It was published in 1999 and it is an account of a long-term study of a group of Hungarian children, aged 6 – 14 and analysing their motivation to learn English at school. Professor Nikolov gave out the questionnaire to her students, which the kids filled in (in their L1) and which was followed by a feedback session with the kids.

Without risking that I would deprive anyone of the pleasures of reading the article, I would like to share here my own main take-outs:

- all the reasons to learn English have been divided into four groups: the classroom experience (aka the activities), the teacher (‘my teacher is short’), the external reasons (aka the parents and the grades) and the utilitarian reasons (aka the future) (p. 42)

- all these were present in the answers given by different ages but it was possible to distinguish three sub-groups: grades 1 – 2, grades 3 – 5 and grades 6 – 8

- the attitude to English (one of everyone’s favourite subjects) was compared with the attitude to the other subjects

- a whole range of favourite classroom activities was revealed and a range of nobody’s favourite activities such as tests, acting out and (this one made me laugh) boring stories

- in response to the final question (‘If you were a teacher, what would you do differently?), some kids suggested abandoning tests, some felt that the teacher should be stricter while dealing with different classroom management issues but many didn’t want to change anything at all.

- the connection between the school grades and the motivation. On the one hand they are the extrinsic motives, on the other hand, as professor Nikolov says, ‘achievements represented by good grades, rewards and language knowledge all serve as motivating forces: children feel successful and this feeling generates the need for further success‘ (p. 46).

A source of inspiration, no metaphors

When I first found the article, I wanted to read it precisely because of the title. It made me smile because this quote is perfect and it reveals a lot of how the kids see the world. Plus it is a fantastic way of drawing the attention of the readers-researchers whose passion are YL. Then, I started to read, curious what I would find them. Finally, it struck me that I did not know what my students would say and that is because I had never asked them.

I was mortified that, in a way, I had taken my kids for granted. Yes, we had been studying together for years, their parents had been bringing them, year after year and there had been no issues, we had fun and we had made progress. But I had never actually asked them.

Naturally, I decided to change it and professor Nikolov’s research was my inspiration and my guidance.

My research took two directions:

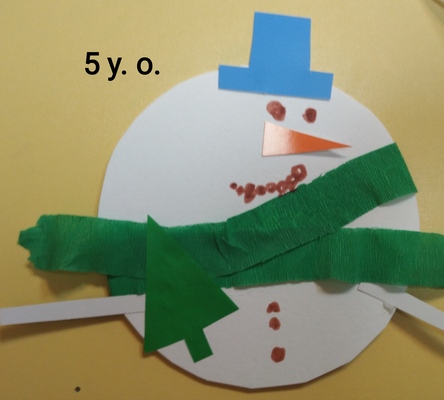

a) I prepared a questionnaire for kids and I used exactly the same questions that professor Nikolov used with her students. I wrote them in English and in Russian and the kids were told that they were able to use whichever language they wanted. The funny and the most amazing thing is that some of my A1+ kids tried to express some of their thoughts in the target language.

b) I prepared a questionnaire for the parents, too, partially because some of my students were 4 y.o. and beginners and, partially, because I wanted to find out what kind of an impact the home environment has on the kids’ motivation. The parents were asked to answer the following questions: Do you do anything in English at home? Does anyone else speak English? Before starting to learn English, did you have a conversation with your child about it? What did you talk about? Do you know what your child likes and doesn’t like about our classes and about their English classes at school.

‘How come I never asked before?‘

…is something that I still keep asking myself. Apart from an opportunity to exercise my almost non-existant researcher skills, this questionnaire and this adventure gave me a fascinating opportunity to see the bigger picture and to become more aware of everything that might have an impact on how my students see the language learning process.

Here are are few insights:

- most of my educational parents admitted to chatting to their kids about the reason to learn English, although sometimes the kids, due to their age, were not quite interested.

- some of the preparation was done in a rather informal way as English as a means of communication entered their lives anyway since they had an opportunity to travel abroad, they were visited by parents’ friends from abroad. They could also see their relatives use English at work or at school.

- some of my younger kids already expressed some of the utalitarian reasons (‘he wants to work for Lego or Hot Wheels’), this was a lot more common among the older students

- the most interesting fact was that for many of my students English was not only a subject, something that belongs strictly in the school. Rather than that, it was a family thing, something you do with mum or dad or with the siblings, younger or older, although, none of the kids came from bilingual families.

- as for the kids, their reasons could be divided into the four groups highlighted by professor Nikolov: the external (‘My mum told me to’), the utilitarian (‘I will travel to different countries and cities’), the teacher (‘Because of Anka’) (insert a million hearts here) and the classroom (‘Because I like it’)

The follow-up?

Raising the awareness and finding out is only the first step and it highlights the importance of a few processes. Naturally, the teacher has no influence on the background of the students or on the family social status and their ability to travel abroad for example. However, the teacher can make sure that the parents are involved in the classroom activities and classroom life, to the extent in which it is possible and, at least, those parents that wish to be involved. This can be done through helping to take English out of the classroom and extending the exposure by sharing songs, games, activities and keeping the parents informed.

There are also some opportunities to bring the world into the classroom, especially nowadays, in the post-covid, zoom world by using the real life materials, traditional stories, guests, virtual guests, pen pals etc. This way, even without travelling, kids will see the connection between the coursebooks on their desks and the world out there.

There is a lot that the teacher can do as regards including the age-appropriate activities, finding out what the favourite activities are and working on building the community even if only by learning the kids’ names, celebrating birthdays and creating the new, group-specific traditions and ‘traditions’.

The first step can be reading about professor Nikolov’s study and running your own research and finding out why your students like to learn English…

Happy teaching!

P.S.

Fun fact? This blog was created as my reward for completing the MA programme. I submitted the final version of my dissertation around midnight on the night of the 1st and 2nd of March 2020 and, on the 2nd of March, during the day, when I did catch my breath a bit, I got my funky socks and my dragons in line…

Bibliography

Marianne Nikolov, ‘Why do you learn English?’ ‘Because my teacher is short’. A study of Hungarian children’s foreign language learning motivation. Language Teaching Research, 1999:3:33, p. 33 – 56