What do you mean you can’t suddenly land on Mars? Sure you can! You get ready for something else, as far from space travel as only possible, you arrange all the bits and pieces, you make your copies (because you assume you are preparing for teaching) and then, suddenly, due to a combination of factors (although the Russian phrase стечение обстоятельств somehow fits better here), you open your eyes, you open the door of what turns out to be a rocket and, ta dam, you find yourself on Mars!

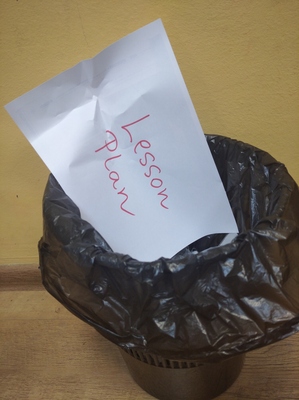

Naturally, everything that you have prepared, on paper or in your head, is, all of a sudden, absolutely useless. The whole lot of it, so, immediately, it lands in the bin or, what we refer to as with my kids, ‘Our Tresure Chest’. Hence the photo.

Congratulations! One of the most amazing adventures of your teaching life (probably) is about to start in…3…2…1…

What really happened?

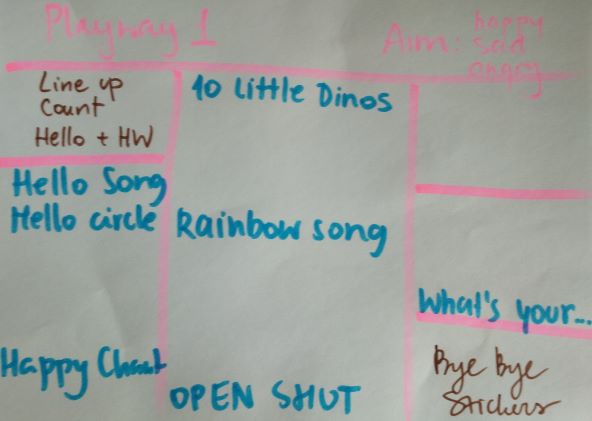

It was supposed to be a short summer course, for kids, primary, whose main aim was to be a revision and reinforcement of everything that the kids knew, based on games, speaking activities and project. It was a programme I prepared myself, a programme I had run in the past, a programme that had been tried and tested. There are no coursebooks.

However, on the day, due to this amazing combination of factors, all of a sudden, there are four great kids sitting in the classroom, a ten-year-old, a seven-year-old, an almost-seven-year-old and a five-year-old. As regards the levels, one of them is more of less a Starters level and three false-start beginners which means that they know an occasional number, a few colours and a pet or two. Plus, they have had some exposure so, rather than run away, they make an effort to listen and to follow instructions.

Of course, since it is the first day, they trickle into the classroom (a new routine is building up, also for the parents) and the lesson takes off three times in a row. It is an interesting feeling to become aware of the fact that the lesson is 120-minutes long (or very very long), especially when you have nothing ready.

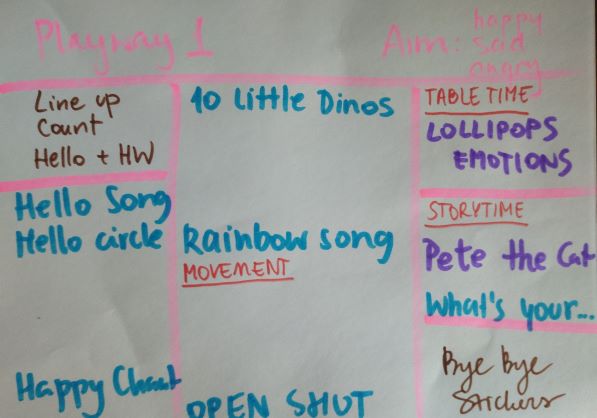

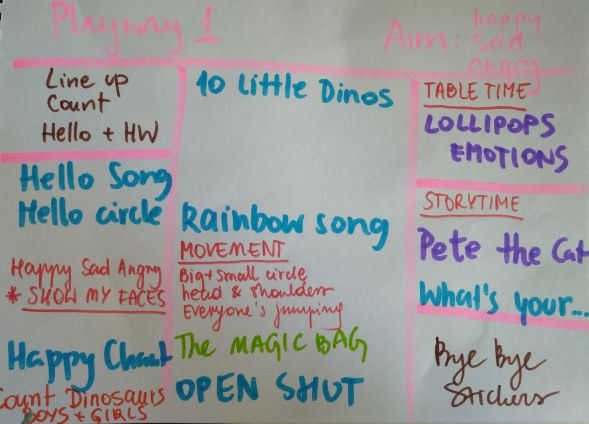

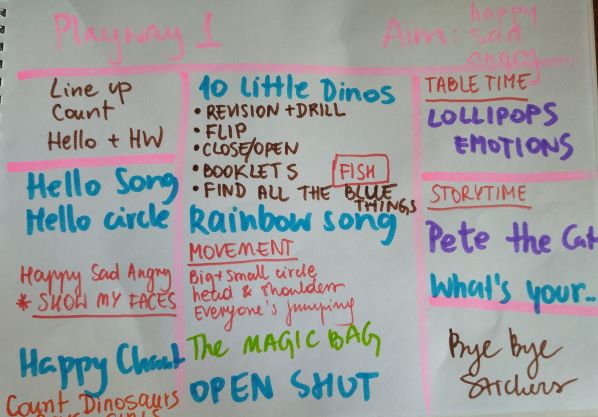

By nothing, I mean ‘literally nothing’. All of the materials and the lesson plans I had prepared were lying on the nearby table, I could see them from the corner of the eye throughout the lesson. I knew that they were entirely irrelevant at the moment and that maybe, if I am lucky, I might use them later on, with some other group. Maybe, not during this particular lesson that I was very much a part of and responsible for.

What I learnt from this experience

Spoiler: Plenty.

First of all, finally, I was able to pinpoint what ‘being experienced‘ means. It’s been a while since I started teaching and another while again since I could label myself as ‘experienced’. At the same time, I have never really thought what exactly it means to me. Because, normally, you don’t think about it, do you? Unless, sometimes, you are asked to add the number of your teaching years while putting together a bio for one conference or another…Or when you bump into ‘a student of yore’ and you notice how much they’ve grown. And how much time has passed.

I was teaching, peaceful and quiet, thinking that ‘It’s ok. Everything is going to be alright. The patient will live’. I was not happy because I really hate coming into the classroom not having planned my classes. I was not excited about the potential challenge and an opportunity to experiemnt and learnt. But I was angry, scared or even stressed out, just teaching. Anyway, the kids were in the classroom already so, if not for anyone else’s sake, it would be recommended that I behave for them. I don’t know if it works for everyone in the exact same way, but for me, yes, the students’ presence (insert here: kids, teens, adults, trainees) has a calming effect on me. All in all, that would be the definition of ‘experienced’ for me.

Then, this particular lesson (or the course) has made me think again about the case when students, who belong to different age groups but study together. Of course, there is a reason why we take these two factors into consideration: the age and the language level and we want to provide the best service, always suited to the individual students’ needs. There is no doubt about that. However, at the same time, over the years, I have been in a situation when the younger were together with the older and it did work. Because it did work in that case, too. It has worked, rather, (we are not done yet) and I am trying to understand why and how.

I don’t fully understand it yet, I am collecting evidence, so to speak, but whenever that happens, I always think of siblings playing together and doing things together, despite the age gap.

The most interesting part of it was the teacher’s brain at work. At one point in the lesson, I realised that it was working on as many as four levels simultaneously. One – because I was actually fully involved in the activity that was taking place at the moment, a game that we were all playing. Two – because I was thinking fast on my feet, trying to plan the next few activities, until the break. Three – because there was also the second half of the lesson after the break and I had to plan this part, too and four – because I was doing all that and also reflecting, on the go.

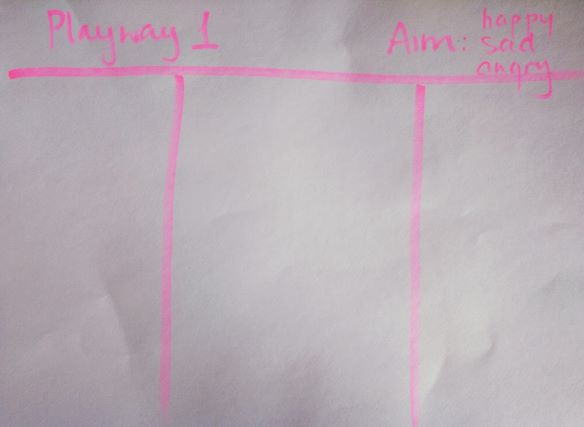

It was not all about killing the time and making sure that the kids leave the classroom alive and kicking, happy and healthy. It was about making sure that the children learn something and that we meet our lesson aims, although, admittedly, these were the aims that were set in the course of the lesson. All in all, it was a successful lesson. We learnt and practised some vocabulary and the kids learnt the room as humans who can use ‘I like’, ‘I don’t like’ and ask the question ‘Have you got?’ because we needed it in a game. If I had been observing this lesson, I would have given myself a ‘To Standard (strong)’ or maybe even ‘Above standard’. What a relief:-)

The only problem with it is that the brain gets really, really tired with such entertainment. As soon as the kids left, I just slumped on the desk and took a 15-min power nap, then lunch. Then, I was good to go, as if nothing ever happened.

Coda and the follow-up

Last but not least, it made me think about all the less experienced teachers and how they might react in such a situation and what I could tell them to help deal with the stress and the students in such a situation.

For that reason, next blog series will be about that, landing on the teaching Mars and surviving. I am planning a post on the top ten resources that might come in handy and that will help to save the world (kind of) and on a three posts in which I am going to share my ideas for the lessons based almost entirely on paper. Soon in cinemas near you!

Happy teaching!

‘