Meet Ela, a newly qualified, inexperienced VYL/YL teacher, from Poland, who has just completed her CELTA course and who is about to start a new chapter of her life, as a teacher of English.

Ela is lucky. She is starting not only one but two new jobs next week and both will involve working with very little people. One is in her hometown and it will be face-to-face, the other one online, in China. Ela is a bit nervous, because it is a new job and because she has never really worked with kids before. There will be some induction or orientation at both places but it is only to take place next week.

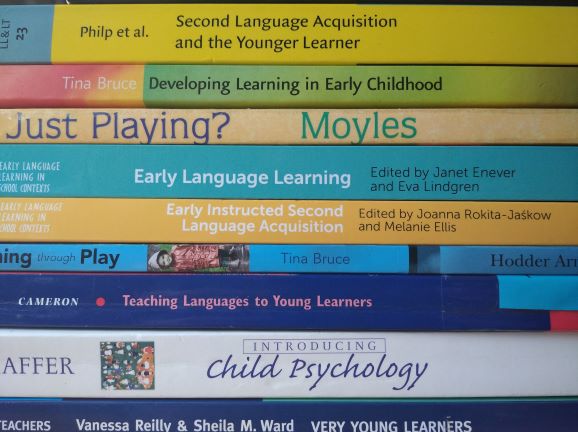

She is also lucky because there is still some time left AND she has got access to more than just google. Her teacher training centre is in her hometown so she can just walk in and do a bit of research and reading in the library there. She hasn’t even started to teach and she already has lots and lots (and lots) of questions.

What about the L1 for example, the students’ mother tongue? Should the teacher use the L1 in class? Or outside of class? Should the kids been allowed to use L1 in class? Should they only use English? Should the teacher know the students’ first language?

Ela is a newly qualified teacher and so her way of compiling a reading list is not a perfect one but here some of the ideas that she has come across…

Herbert Puchta and Karen Elliott, Activities For Very Young Learners

This publication is a compendium of activities and ideas for the classroom but it includes a brief introduction with some of the principles that should be taken into account while working with the pre-school children. Puchta claims there that the knowledge of the L1 on the C2 level is absolutely necessary in order to help clarify any problems with comprehension as well as to assist the children in case a problem occurs.

What does Ela think now? Well, she is grateful for all the practical advice on how to avoid using the L1 in class but, at the same time, feels like she is doing something wrong or even illicit. After all, she was offered this job in China and not one person ever asked any questions about her level of Chinese. Then, she is thinking of her best friend, Kasia, who left for Japan and taught kids there, and Anya who landed in South Korea…her CELTA tutor who used to teach in Mexico and one of her CELTA peers, Jessie, who worked in Poland and that none of them spoke the langauge of the country where they worked and definitely not on a C2 level. Not even on an A2 level, to be honest. Ela is confused.

Opal Dunn, Introducing English to Young Children: Spoken Language

No, scratch that. Ela only thought she was confused earlier. Now she really is, after having gone through a few pages of the Opal Dunn’s publication.

First of all, it is because she has found out that children cannot bond with a monolingual teacher (that is a teacher who does not speak the children’s L1) and that they might get disappointed and frustrated. It does not bode well for that online job in China or for any other future positions abroad but at least that’s some good news for the groups she is going to teach in her hometown.

The rest, however, is a bit more difficult to digest because translation, at the same time, must be and mustn’t be used in the classroom. ‘Only English’ should be one of the rules but the teacher should explain it both in English and in L1. The same can be done whenever a new concept is introduced but should be done quickly and in a different voice.

There is also the issue of the kids translating from one langauge to the other. It should at the same time be encouraged (‘as being able to translate is a skill that needs to be encouraged’ p. 134) and discouraged as kids might not tune into the English version waiting for translation (‘the habit to translate should be broken’ p. 136).

Ela is beyond confused. She wishes she had stopped reading on page 134. Or that she had only limited her reading to page 136. Too late!

Vanessa Reilly and Sheila M. Ward, Very Young Learners

Reilly and Ward’s publication is the oldest resource available on the market devoted solely to teaching VYL and for some time it was the only published resource for the teachers who work with the pre-primary children.

Probably the most important line that Ela finds there is the following quote: ‘if we tell the children that they can only speak in English, it is as good as telling them to be quiet’ (p.5), followed by the list of reasons to accept the L1 in the classroom and some practical ideas on how to avoid using it and how to gradually replace it with English.

Ela is somewhat relieved to have found a note that the attitude to the mother tongue in the EFL/ESL classroom might depend on the country and the particular school’s policy. She thinks that perhaps that might, at least to some extent, explain the fact that she and her colleagues were hired to teach despite the lack of knowledge of the children’s L1, although, the authors here, just like everyone else she has read so far, seem to assume that all the teachers working with YL and VYL speak the children’s mother tongue.

Ela is, admittedly, more peaceful now, although she still does not quite understand she even got the job if the L1 proficiency is such an important requirement.

Sandie Mourão and Gail Ellis, Teaching English to Pre-Primary Children

Ela might not know it yet but she is really lucky: as a newly qualified teacher, at the very beginning of her career, she had a chance to read this particular book.

The authors outline ten principles of teaching English in the early years and the principle number 2 refers to L1: ‘Children will sometimes use their home / school language when learning English, which is viewed as part of the natural process of language aquisition and evidence of learning’ (p. 214) and they provide a list of situations in which both the teacher and the students might feel the need to resort to the L1 in the EFL context. Ela takes notes as she might need this knowledge to understand what is going on in her classroom. She especially likes the questions for self-reflection, such as ‘Why and how did I use the L1?’, ‘Could I have done it differently?‘ (p.215) or, as seen from the child’s perspective ‘What steps did I take to help the child move from L1 to English‘ (p.215).

Elat is happy, she finally feels like she has learnt something. She is not as nervous as she used to be. There is only one question that has been left unaswered and that refers to al these teachers who teach preschoolers without speaking their L1. They exist and Ela is one of them. Only now, she is too excited and she only wants to go on reading. This is where we are going to leave her now… Enter the Dragon (teacher/trainer), me with only a few facts from the VYL kingdom with a few summarising comments.

At the moment, there are altogether 4 volumes devoted to teaching pre-schoolers. Reilly and Ward published their compendium in 1997 and it took twenty years (as in 20, as in two decades) for another title to appear on the market in 2017 when Puchta and Elliott came out. All that despite the fact that this area of the market has been growing in strength all this time (Garton and Copland, 2018).

The latest addition, by Sandie Mourao and Gail Ellis has just been released and it willl take some time for it to make it to all the libraries, teacher training courses reading lists, bookshops so it might be that some newly qualified teachers will be walking into their first lessons without having read it. But the good thing is – the book existis and it is available. The newly qualified VYL and YL teachers, the VYL and YL novices, the Elas of today are indeed lucky. They have a lot at their disposal and a lot more than the Elas of five or ten years ago.

Even in the areas that are and have been ‘hot’, ‘popular’ and well-researched, it takes forever for the findings to permeate into the coursebooks and the mainstream consciousness, let alone areas like ours that is considered ‘a niche’, at least by some. As Sandie Mourão writes (2018) ‘Precious little research involves pre-primary FL learners, so research in any direction would be welcome’. Yes, ‘precious little‘ and ‘any‘…Things have started to change, slowly so it will probably take another twenty years and a few more dedicated teachers and scholars before we have answers to some more of the VYL questions. Those related to the presence of the L1 in the EFL classroom but not only those, of course.

In the meantime, there is still more to come in this series here, some studies that I have come across as well as the findings of my own small scale study on what the VYL teachers think of the L1 and what they do…See you in a bit. Oh, and if you haven’t done it yet, check out the introduction, too!

PS I am really interested in the attitudes of primary and pre-primary teachers to using the kids L1 in class, by the students and by the teachers. This was one of the beliefs that I was researching in my MA dissertation (the post on that coming up in this series). The MA is done (yay) but the research continues so if you have a few minutes to spare and you don’t mind taking part in the survey, please follow the link and answer a few questions here.

Bibliography

Photos courtesy of Юлец

* )W.Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, act II, scene I

O.Dunn (2013), Introducing English to Young Children: Spoken Language, Collins

Garton, S. and F. Copland (eds), (2018), The Routledge Book of Teaching English to Young Learners, Routledge.

S.Mourão and G.Ellis (2020), Teaching English to Pre-Primary Children, Delta Publishing

S.Mourão (2018), Research into teaching of English as a Foreign Language in early childhood and care, In: S. Garton and F. Copland (eds), The Routledge Book of Teaching English to Young Learners, Routledge, p. 425 – 440.

H.Puchta and K.Elliott (2017), Activities for Very Young Learners, Cambridge University Press

V.Reilly and S.M.Ward (1997), Very Young Learners, Oxford University Press