Preface

A while ago I got into a discussion on why the realistic flashcards aka photographs are much better for YL than the cartoon flashcards.

Oh wait, not quite this way. First (and foremost), as I am typing up this post, I am glancing left and right, for support. To the right, towards the shelf with my storybooks and all the ‘unrealistic’ illustrations and all the imaginary characters and to the left, where the materials for the next Lesson at the Museum are lying (this week: Natalia Goncharova, more of that – soon!). At this point, I still cannot formulate it very well but my guts (and a few years in the classroom and around kids) are telling me that realistic and photographic IS NOT the only way. I object.

Second of all, this discussion, it just was not a discussion at all. I must admit, I am a bit naive when it comes to the social media and I would like to believe that teacher meet there to exchange ideas, to learn from each other, not to preach, making it look like theirs is the only way to do things and recommending that I should do my homework and read first before I voice an opinion (as if the empirical evidence did not matter at all).

Enough of this bitterness, though. Here I am after all, doing my own reading and research, with mixed feelings, if I am to be perfectly honest. A little bit anxious (because what if the research proves that I was wrong, eh? What then? (I am laughing here) and a little bit excited (because what if the research proves that I was right? (still laughing).

This introduction was planned and written before the actual reading did happen but you, dear reader, looking at the title (courtesy of Mr W. Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon), you can guess now where it is all going (based on the research that I have managed to do so far) so if you have very little time on your hands, I will make it easier for you, here is a summary of the whole post:

When it comes to choosing between the visuals with a high degree of iconicity (aka the resemblance between the picture and the object) such as photographs and the visuals with a low degree of iconicity such as cartoons, storybooks illustrations, there isn’t only one answer, one way out, one approach. It is not a case of black and white, good and bad, left or right. It is a beautiful case of ‘well, it all depends’. Done.

Now, if you have more time, follow me. There is more to come.

Act I: Why choose the real photos

The first (and the most important question) to ask here is: How old is the child? A picture is a symbol, a representation of the real object and children will require a certain level of cognitive skills development (such as symbolic development, analogical reasoning, reasoning about fantasy and reality) in order to be able to process that image and to relate it to something that they know from real life.

For example, newborns, who have not become symbols users, when presented with a photographic image and a real object, would always choose the real object over the visuals but, at the same time, if the real object was not present, they would interact with its image in exactly the same way as they would with the real object. These examples come for a truly fascinating article by Gabrielle A. Strouse, Angela Nyhout and Patricia A. Ganea which you can find here.

As shown in other studies they mention, too, it seems that although these young children can transfer the concepts both from cartoons and photographs or realistic drawings to the real world, the more realistic the image the easier the transfer. And for that reason, we find plenty of recommendations for such books to be used with the younger pre-schoolers. This attitude seems to be especially popular according to the Montessori method (although to be honest, I am not very familiar with it, I know it only from reading, not from the classroom, so forgive me for any inaccuracies or faux-pas that I might commit here).

Another interesting argument, and this time applying to not only the youngest children, is how the information presented in the picturebooks might have an impact on children learning about the world. As Strouse (et al) claim, it seems that ‘Fantastical context used in stories may cue children that information presented in books is not transferable to real-world contexts’, especially when the children do not really have any opportunities to connect the book world with the real world because, for example they live in the city and have never been on a farm, or are not supported by adults in their journey through books. The authors claim that it might impact the learning of physics and biology or moral learning. All these arguments would support the use of photographs and realistic cartoons.

Apart from that, there is the obvious argument, applicable both to children, teenagers and adults, alike – we like photographs. According to the professionals such as graphic designers (because this is where this reasearch has taken me, too), photography is used when we strive for accuracy, professionalism and when promoting the object is the real aim. The latter two might not really be relevant to the world of EFL and ESL but the first of them, accuracy is going to be our key word. When presenting vocabulary to children we want them to understand clearly what we mean and a photograph of an elephant will illustrate it better than a drawing of an elephant. We might not only see the tiny little details such as the shade and the texture of the skin but, quite likely, the elephant will be photographed in a natural environment so we will be also able to notice how big it is and what kind of a habitat it lives in. The elephant will most likely be doing something, walking, running, eating or sleeping and this will help us understand a bit more about it. Not to mention that it will also help us produce more language (the secret aim for anything that the English teachers do).

It seems to be especially important in the English lessons while teaching the concepts that students are not familiar with and which they do not encounter in their real life such as the jungle animals (while teaching in Russia), snow (while teaching in Brazil) or Polish pierogi (while teaching outside of Poland). The photographs will help the children understand these concepts better than drawing, although, it has be said that no photographs of snowy landscapes will help you get the real idea of what winter is like unless you have rolled in snow yourself and unless you have actually tried to catch the snowflakes on your tongue. As regards preschoolers, there arises one more question, too – Should we even introduce the concepts, ideas and vocabulary that they are not familiar with in their L1 and in their lives? My personal (and very subjective) answer would be: ‘no’, not in the EFL context, with a limited language exposure and the limited lesson time available. With a very few exceptions, of some cool animals. Perhaps.

Act II: Why choose illustrations

First and foremost, as children are growing, they develop their cognitive skills and they become better at recognising symbols, using symbols and, last but definitely not least, at creating symbols (here you will find my earlier post devoted to symbolic representation and the EFL with your starter kit). Using illustrations, cartoons and drawing is necessary!

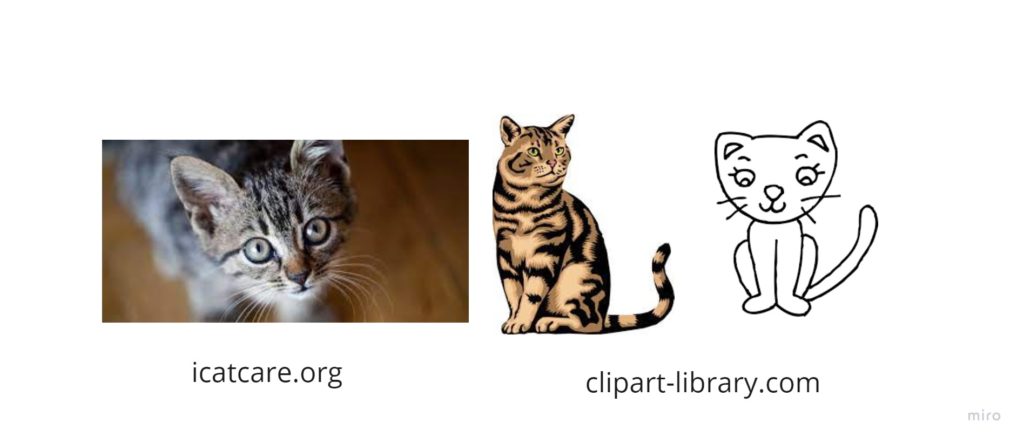

Children are progressively better able not only to distinguish between these and label them as more realistic and a less realistic representations of an animal…

…they might also appreciate the cat on the far right as it is most likely to resemble the cats that they draw in their pictures. And as they are learning to hold a pencil and to produce marks, scribbles, lines and circles, it will be quite a long time before their drawings look like the cat in the middle or anywhere near the cat on the far left. As Bernadette Duffy (see bibliography) says ‘If we intervene with a view that the purpose of art (or, in this case anything that children create (own comments) is to produce an image that is as realistic as possible and therefore think of children as failed artists we may do great harm by imposing inappropriate expectations that do not match children’s developmental stage‘.

Then there are the visual arts and these are full of ‘hurdles’ for a rational mind. Picasso’s faces are far (far far) from realistic. Chagal makes his characters float in the air, as if they were kites (sometimes accompanied by goats). Warhol stubbornly chooses the ‘wrong’ colours and Malevich replaces the whole world with one (amazing) square. And then there is Miro, Bosch, Rothko and many, many, many more. It is, of course, possible to give up on teaching art to such young children, but, before you do, please read why it is a good idea and how it benefits them. For that very reason, all the major galleries and museums include programmes for kids.

As for the graphic designers, among the advantages of the illustrations is the fact that they can be used whenever it is necessary to show the unique features and to stand out, since all the photos of the cat might look the same and the drawings will differ as they will depend more on the artist style, abilities and techniques, when a simple design is needed (for example an icon) and to depict the imaginary.

The last argument seems especially fitting in the world of the early years. Or in the classroom. Children love stories and these feature real children, talking animals and a whole array of imaginary characters such as mermaids, fairies, dragons, dwarves, fish with fingers and children who are going on a bear hunt (something that you should not really be doing in real life, not when you are five and, actually, although this is yet a very personal opinion, never ever ever). This imaginary world is a part of being a child and children do grow out of it, eventually and naturally. Although, still, some of us, even at 40, we like to revisit this world, accompanying Harry Potter to Hogwarts, Frodo to Mordor and Zima Blue in his search of the meaning of life.

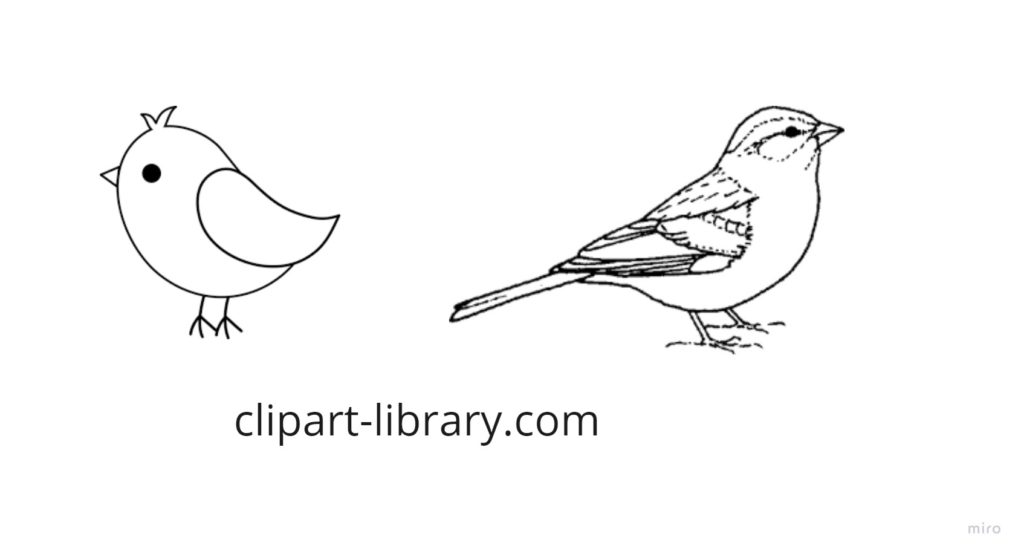

Another thing is that, as a material designer for preschoolers (and I am that, too, as all teachers are), I sometimes tend to choose illustrations over photographs specifically because they are simple and easier to colour for my 3- and 4-year-olds and because I want to convey the general meaning of the word ‘bird’, rather than anything specific, for instance ‘a sparrow’

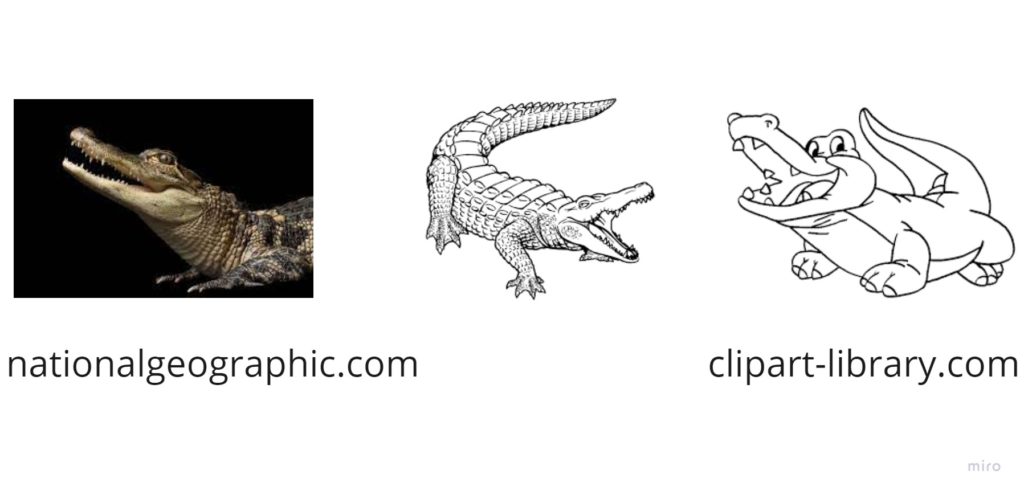

Another reason for choosing the illustrations over more realistic drawings or photographs is that some animals look too realistic and scary. I am one who does not really like touching the spider flashcard (cartoon, but too real and disgustic) and some of my students feel the same way. So, in case of a crocodile, for instance, I might opt for the one on the far right.

Act III: Why do we have to choose? Variety is the answer!

That’s it. A ridiculously short Act III. Nothing more to add. We can and we should use both. Also because the realistic is not always true, either. Have a look at the photo that introduces this post once more: Am I or am I NOT sitting inside of a huge glass piano?

I hope you have enjoyed reading this article as much as I have enjoyed researching for it and that this is definitely not the end.

And a request to you, dear read. All of the sources that I have used directly have been referenced throughout the post. Below you will see some other treasures that you might find interesting. If you have anything else to add to this list – please, let me know in the comments sections.

Two requests, actually – if you have any stories related to children’s reactions to the photographs and visuals used in class, more or less realistic, please share these, too!

Happy teaching!

Много шума из ничего (1993) – IMDb

Bibliography and further reading

All the sources that I have quoted have been referenced throughout the post.

Here are some more things that you might want to read

Why children need real images – how we montessori

Drawings – stages, meaning, Definition, Description, Common problems (healthofchildren.com)

An introduction to the visual arts in early childhood education – THE EDUCATION HUB

Teaching Preschool Art Lessons — KinderArt

Around the world: Art allows all children the freedom to explore (pearsoninternationalschools.com)

Why Real Photos? What about Cartoons? (stageslearning.com)

Picture This! Why Books with Real Photos Help Kids Discover the Big, Wide World (kindercare.com)

Pictures and Images in Flashcards – Are They Even Useful? (universeofmemory.com)

The Truth about Flashcards for Toddlers Who Don’t Yet Talk – teachmetotalk.com

The Pictorial World of the Child (nih.gov) (a review of a wonderful book that I am getting as soon as I can come up with a reason to treat myself)

How to Introduce Toddlers and Babies to Books • ZERO TO THREE

Which Works Better: Illustrations or Photographs? – Ecommerce Platforms (ecommerce-platforms.com)

5 Reasons To Choose An Illustration | Holywell Press

Bernadette Duffy, Supporting Creativity and Imagination in the Early Years, Open University Press, Maidenhead

P.S. A request!

It is very simple.

I would like to know a tiny little bit more about my readers. There are so many of you, popping in here, again and again, and the numbers of visitors and visits are going up and make my heart sweel with joy. But I realised I don’t know anything about my readers and I would love to know, a tiny little bit more.

Hence the survey.