My name is Vader, Darth Vader. I am a teacher and a teacher trainer, I work with VYL and YL teachers.

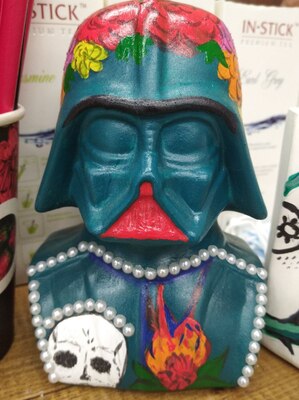

Well, not really. I would like to think that, as a trainer, I smile a lot, I am supportive and open to questions and debates and I only shout at football matches. But there are those moments, on the courses that I teach or just in the everyday mentoring life, when I feel I am taking on some of Mr Vader’s traits. Although even then it is more in the style of the Darth Vader in the photo above.

One of those Darth Vader moments is defnitely induced by some of the concepts and beliefs related to teaching English to young and very young learners. They are out there, in the world, and although they are entirely ‘wrong’ or ‘incorrect’, they have already become some EFL YL clichés that can cause more harm than good.

In the post below I will share with you my top five ‘Think Twice Concepts’ in the early years EFL. A very subjective approach, I must warn you. Are you ready? Fasten your seatbelts! Let’s go!

Bad behaviour

There is nothing that could be labelled as ‘bad behaviour’, not in the EFL classroom full of pre-schoolers. There is curiosity put to practice, there are emotions in action, there are boredom- induced replacement activities. There is fear that materialises itself as agreession and a general lack of goodwill. There is tiredness, hunger, possibly, or, on the contrary, the high levels of sugar from the chocolate bar eaten five minutes right before the lesson or the memory of the morning visit to the doctor and the unpleasantness of it that still lingers in the air (although the arm really did stop to hurt after a jab about three hours ago). There are, also, plenty of examples of ‘I will do what I have always done in such situations and if it has always worked so far with mum, with nanny, at home, at pre-school and at the playground, it is bound to take the required effect here, too!’

There is no bad behaviour, although sometimes we get to deal with ‘the unwanted behaviour’, that might be getting in the way of our lesson or other children’s physical or mental well-being.

Solutions: first of all, react, ideally to stop this unwanted behaviour, or, at the very least, to signal that it is not what we want to have. If one thing is certain, it is that it is not just going to happen, all by itself. Then, after the lesson, when everyone has already left and when the dust has settled – reflection. Was the first time that it happened? Does it always happen? Is there any chance that some triggers could be identified? Was it in anyway related to the activities, to what the teacher did, to what other children did? What happened later?

It is always a good idea to talk to the parents or carers, too. Not to complain or to blame the child or the adults but mostly to understand what really happened and why. And perhaps (but just unfortunately ‘perhaps’) this information will come in handy the next time it happens.

Egocentric

I don’t think I will ever be able to forgive Piaget for using this particular adjective to describe the little kids’ attitude to the world and to the people in it. It is a perfect example of a concept created by adults and used to refer to people who are not adult yet and whose attitudes and reactions are what they are simply because they have not had a chance yet to grow and to develop fully. In the EFL terms, it would be like sending a seven-year-old beginner to take an FCE exam and then scolding them for failing while they are simply not there, not yet and they should be seen nowhere near the exam room.

Of course, pre-schoolers might struggle with sharing the box of crayons, they might want to always be first and always hold the teacher’s hand. They may not like to sit next to Pasha today and they will not want the other children to touch the car they brought to class, to show off a little bit. They will not be happy about leaving their picture in the classroom for the teacher to display on the noticeboard. And they will all want the princess flashcard. But all of that happens because they are just learning how to be a person in the world full of people and a person in that particular group of children learning English.

Solutions: The most important of them comes from Mick Jagger because, indeed, ‘Time is on my side, yes, it is!’. The group of children starting to study together in September will be changing, from lesson to lesson, and even after a week or two or three, they will be a completely different bunch, only because they have had a chance to interact with each other, to do something together and to find out that a group is not Anka and five other someones but Anka and Sasha, Pasha, Kirill, Mitya and Olya, some of whom we like a little more, some of whom we like a little bit less.

Apart from that, there are also all the tricks that the teacher can use throughout the course, to help the little people bond and start noticing the other children and start to learn how to share the lesson with them.

So, no ‘egocentrism’ but ‘social skills that are still developing’.

A typical five-year-old child…

Apart from the knowledge of the language and the knowledge of the methodology, the knowledge of the child development stages is one of the three areas that an EFL teacher working with young learners needs to be familar with (Mourão, 2018: 429) and it is great to see that a summary of these characteristics have made it into the professional literature ( Mourão, 2020: 33 – 39) and are easily available online.

At the same time, there is a danger that teachers will be looking into these and applying them too religiously, without considering the differences between the individual children. As Mourão (2020: 215) says ‘Children develop holistically, show individual differences in development and progress at different rates’. That means that even if we had a group of only five-year-olds, all of them coming from similar environmenta and all of them provided with the same opportunities and, even, why not, all of them born on the same day, they could all develop their cognitive, motor, social or linguistic skills at completely different rates. As a result, despite the fact that the group would be theoretically homogenous, a teacher would still have to deal with a mix of abilities. It seems that a teacher equipped with a little knowledge and induced by this knowledge expectations of the children and of the lesson might be even more damaging that no knowledge at all. Because typical five-year-olds don’t exist.

Solution: an open-mind and an organic approach to the little people sitting in the classroom. Instead of applying strict frameworks and checklists and trying to make the kids fit in the tables (which they are more than likely not to be able to do, as a group or as individuals), reading and researching the age group in a close connection with the specific students whom we teach at the moment.

Short attention span

This is, without any doubt, one of the most important differences between an adult and a child learner and this is the one that gets highlighted most frequently. For a reason, too.

However, at the same time, any attempt at specifing what that attention span is or, even more, at quantifying is, simply, pointless. Much as it may give the (false) impression that once the concept has been assigned a number, it is not as scary and it will be easier to deal with, especially for those of the teachers who have little or no experience of working with the younger children. It is from them that I often hear that ‘an activity should not take more than five minutes’ or, even, ‘it is the child’s age plus one minute’.

Well, I wish it had been that straightforward.

In real life, the attention span will be very much dependent on a number of factors that nobody is able to predict or enlist, and, as such, it is simply impossible determine once and for all. Children’s attention span will be related to their age, to some extent (although it will materialise itself in a way unique for each child) but it will also be affected by absolutely everything that might have had an impact on the children’s mood before and in the lesson and the teacher’s mood before and in the lesson. Such as? Such as the first snow of the year, a spider in the classroom, a visit to the doctor just before the lesson, a swimming lesson just before the lesson, a birthday party attended, a grandma’s visit, candy eaten before the lesson…Or a teacher who has had an especially tiring or stressful day, any malfunctioning technology or a handout lost. Any of these and the tried and tested activity that has always worked with the same group or the same age group, that has had the kids in awe and involved for five or even ten minutes, can quickly turn into a failure or the most boring and unappealing activity in the entire world.

Solution: first and foremost, switch off your adult thinking of what happens in the classroom. The kids, young or very young, they will not be just sitting behind the table, patiently waiting for you to start what you have prepared for the day AND they will not stay involved in it for a prolonged period of time as long as you think they should. Second, while planning a lesson, think about it from your student’s perspective and ask yourself what your students might find interesting about an activity. Is there anything that would motivate them to engage in in? Anything else that just the mere fact of this being an activity done in a lesson.

Then, in the lesson, itself, keeping your eyes open and adapting to who (and in what state) you have in the classroom on the day is the best way of dealing with all the implications of the short attention span. And, although I would argue that this applies to all the age groups and levels, being ready to let go and teaching the students and not the plan, not the coursebook, not the handout and not the activity.

‘They don’t like singing’

Sorry, permission to disagree here and yes, even before I have seen you in the classroom and before I have met your little students. I don’t think it is true, simple as that. Why do the teachers say that then?

Partially, it is because, again, the adult perception of what song and singing is and should be gets in the way. On the one hand, when we listen to songs in our non-teaching life, we do just that, we listen and take pleasure in it, hopefully. There is nothing wrong with it, and, indeed, I believe that listening for pleasure should be sometimes included in our lessons, too. The only ‘problem’ with very young learners is that they might not be familiar with that kind of an exercise and after a minute or two, with no other task, they will be getting bored and distracted. And, possibly engaging in other, unwanted, activities.

On the other hand, when we use songs in the EFL lessons, we expect the students to sing these songs and in case of pre-schoolers or even primary school children, it will take them for them to master all the elements of the song, the music, the rhythm, the lyrics, before they are actually ready to sing. If the teacher expects a real performance in the lesson in which the song was introduced for the first time, they will be disappointed. Again, the children might remain focused for a minute or two and then, again, they will find something else to do and the teacher will arrive at a conclusion already mentioned in the heading to this paragraph.

It is true, that the word ‘singing‘ could be replaced with absolutely any type of a YL activity, ‘craft’, ‘miming’, literacy’, ‘animals’, ‘this game’ and the implications would be the same or almost the same. It is also true that music-related activities are more likely to feature here. Mostly because teachers often worry that they themselves cannot hold a tune or that they are not confident enough to sing in front of others.

Solution: forget about you and your pre-conceptions, your teacher previous knowledge and try. It might be that you yourself are not the world greatest fan of Baby Shark and of pretending that you are a…melting ice-cream (btw, one of the real ideas suggested for the miming game by my students) but the simple truth is, if the teacher does not make an effort and if the teacher does not get properly involved in a song or in an activity, it is almost a given, that the students will not, either. Especially, the little ones. And, really, the most amazing thing about the VYL audience is that they really do not care whether their teachers sing well or badly. The only thing that matters is whether they put their hearts in it or not.

And as for the other problems, be it music or craft, scaffolding and lesson planning is the answer and no two ways about it. If you need any more convincing to why we should use songs with children, please have a look here and if you are looking for some ideas of what can be done with a song to maximise language production, you should definitely look at this post here.

Coda

This post is not only about me having a little venting session on a Monday morning. It is not a critique on the people who use these terms and it is definitely not about my ‘What not to say’ list that I will be handing in to all my teachers and trainees from now on.

I decided to put this post together because it seems that all these clichés start in the very same place and that is when adults try to apply adult categories, labels and concepts to children and to how they see the world, how they learn and how they grow which might lead to misunderstanding, confusion and frustration in the classroom.

Perhaps there should be one more thing added to the list of skills and areas that a VYL or YL teacher should be equipped with, apart from the three mentioned by Mourão (2018)? The knowledge of the subject and of the appropriate methodolody is absolutely crucial and so is the awareness of the child development stages. They are an absolute must and a starting point. Still, they are going to be of little use in the real life if a teacher is not going to be willing to switch the perspective and to try to see the lesson and everything that happens in it from the point of view of a three-year-old or a seven-year-old.

As everything in teaching, nothing happens overnight, and it takes time to develop the ability to observe and to analyse your students and their behaviour and to learn from that. The good thing is that the very willingness to accept the fact that a different perspective is needed is already a big step towards success.

Sometimes, changing the perspective physically can make a real difference, too. In our teacher training courses, we sit at the big tables (of course, we are adults!) but there always comes the time when we transfer to the little stools in a small circle. We do it to practise different games and to reflect on them but this is also a great opportunity to experience how the furniture and the set up can influence the activities and the emotions.

This blog post can hopefully be a good first step, too!

What do you think, dear reader? Are there any other terms that you would add to this list? Please leave your commetns below!

Happy teaching!

P.S. All the amazing animals in the photos live in the streets of Yaroslavl. Mr Vader found a home in a coffee shop Free-da there. All photos – mine, apart from the rooster taken by Юлец and used here with her permission.

References

Development Matters in the Early Years Foundation Stage (2012), to be downloaded here

Mourão, S. (2018), Research into teaching of English as a Foreign Language in early childhood and care, In: S. Garton and F. Copland (eds), The Routledge Book of Teaching English to Young Learners, Milton Park and New York: Routledge, p. 425 – 440.

Mourão, S. & G. Ellis (2020), Teaching English to Pre-Primary Children, Stuttgard: Delta Publishing